|

I began playing ice hockey when I was 7 years old. When I was an orthopedic resident in New York City we formed a Hospital for Joint Diseases orthopedic hockey team. We had the unique opportunity to play outside in central park and also at Chelsea Piers with a view of the Hudson river and the New York skyline.

In spite of the violent reputation ice hockey has, I never personally sustained any significant injury. Until one evening around midnight (we had terrible ice times) when I was involved in a collision deep in my defensive zone. The back of my left shoulder made contact with the boards and I felt a zing of pain into the side of my arm. I immediately had difficulty raising my arm. Thankfully, it was toward the end of the game. I liberally applied ice when I got home, but when I woke up in the morning, I still couldn't actively raise my arm. I was fairly certain my injury was a rotator cuff contusion, and not a rotator cuff tear due to the mechanism of injury, and therefore would be self-limited. This proved to be correct, and by that afternoon, my active range of motion had returned, albeit with some pain. Confident my pain would improve as the contusion healed, I went about my normal daily activities for the next several weeks. I grew somewhat concerned however when the pain wasn't decreasing, but rather it was increasing. As a physician, working with world-renowned orthopedic surgeons who would be happy to assist me, I instead chose to ignore it. My life was too busy to deal with my shoulder. I could work, and for the most part I could compartmentalize the pain. Working at shoulder level or below was essentially normal and pain-free. But, if I forgot and suddenly reached for something, a knife-like jab brought my shoulder's issues front and center. After several months went by, I began to feel that my first choice of treatment (doing nothing) had failed. I finally examined my shoulder objectively and noted that although my strength was normal, I had lost some range of motion. More interestingly, I had lost not only active range of motion, but passive range of motion as well. At this instant I understood why my pain wasn't getting better. I had developed a frozen shoulder. Now everything made sense. At this point, I began my rehabilitation program. Everyday after work I applied ice to my shoulder for about 20 minutes. I purchased an ice machine to assist with this. I tried traditional stretching techniques, but was disappointed with the results. I was able to achieve intense pain, but absolutely no increase in range of motion. I actually felt I was getting worse. Frustration is an understatement. A possible treatment for a frozen shoulder that has been resistant to all nonoperative measures is a manipulation under anesthesia. The surgeon essentially forces the joint through a range of motion, tearing the tight tissues. This is something I clearly hoped to avoid. I recognized that biologic tissues are viscoelastic. I felt that based on this characteristic a stretch done gently, but for longer duration could be more effective. And so I began stretching differently. I measured the duration of stretch in minutes as opposed to seconds. I got to the painful endpoint and held it under tension for as long as I could tolerate it. Knowing that the longer I stretched the better it would be I increased the duration of my stretching to 30 minutes or more. Stretching hurts. I reminded myself that in spite of the pain I was experiencing, I was not creating damage. To maintain a stretch of this duration requires you to relax. The best position for me was to lay on the floor on my back and attempt to simultaneously touch my shoulder, elbow and wrist to the floor at the same time. I added some weight to my hand to increase the stretch and watched TV. I did this routine every day. At first I wasn't sure it was helping. But then I instinctively reached for something without thinking. Something that had previously caused a jolt of pain. And I felt no pain at all. This motivated me to add weight and time to the stretching program. Within a few more weeks my shoulder pain had resolved and I had regained normal range of motion. This method has made surgery for frozen shoulder very rare in my practice. When I first describe this technique to my patients, they seem incredulous. Most have already been through a course of physical therapy and are very frustrated. They presented to me to have an operation. But with very few exceptions (sometimes patients with diabetes have very resistant frozen shoulders), the vast majority of patients can avoid the operating room using this method. I will upload some pictures of how I recommend stretching in an upcoming post.

2 Comments

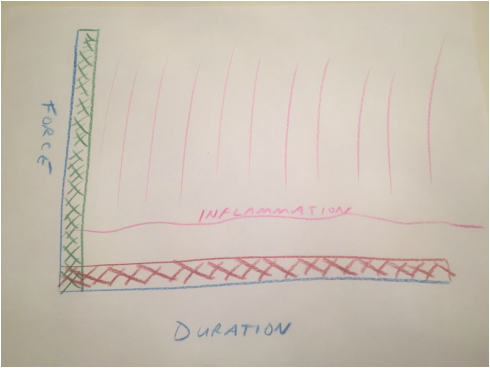

Biologic tissues are viscoelastic. That means their stretchiness changes depending on how hard they are stretched. We can take advantage of this characteristic when we are rehabilitating a stiff joint. This becomes very important with certain medical problems. Specifically: total knee replacement and frozen shoulder. This concept is generally helpful in orthopedic rehabilitation and I take advantage of it whenever applicable. Think of silly putty. When slowly stretched it can be drawn out into a long strand, but when pulled aggressively it will snap and break in two. This is an extreme example of viscoelasticity. Your tissues are similar. While extreme force stretching can cause tissue to tear, this is generally far beyond any amount of stretching a patient can do, even with a physical therapist. A manipulation under anesthesia is a maneuver performed by a surgeon to rapidly regain motion in a particular joint that has become stiff. Tissues tear, and inflammation results. This is the most extreme example of a high force, low duration stretch. It is best to avoid this type of intervention if possible. It is preferable for a patient to spend the time necessary to recover joint range of motion using a long duration, low force stretch. It will result in less inflammation and less pain. Shoulders and knees commonly become stiff. Total knee rehabilitation requires stretching to regain range of motion after surgery. Stretching is required to speed up the recovery of a frozen shoulder. When attempting to regain range of motion patients are often told to stretch for 10-15 seconds and then relax. Over and over. Sometimes this is effective. Sometimes it is not. There is significant genetic variation with regard to tissue strength and inflammatory response, and significant psychological variation with regard to pain tolerance, and ability to relax while stretching. When a patient has trouble regaining range of motion I try to focus them on long duration, low force stretching. This tends to create less inflammation and is more likely to allow a patient to relax the muscles while stretching. Relaxing is very important because any muscle resistance will prevent gains in range of motion.  Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. This sketch depicts how I think about stretching. A high force, brief stretch is more likely to cause inflammation. A gentle prolonged stretch is less likely to create an inflammatory response. The "amount of stretch" or the total area under the curve depicted by the hash marks could be identical, but my experience suggests the long duration, low force stretching will give a superior result. How do I know this? When I was a resident, I developed a frozen shoulder and used long duration, low force stretching to cure myself. I have subsequently recommended this technique to countless patients who presented with frozen shoulders that had failed to improve after many weeks of standard physical therapy. Although occasionally surgical intervention was necessary, the vast majority progressed using this technique and never needed surgery. This technique has become my standard recommendation following total knee replacement and to rehabilitate a frozen shoulder, and has minimized the need for manipulation.

|

Dr. GorczynskiOrthopedic Surgeon focused on the entire patient, not just a single joint. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed