|

While some patients have a very easy time rehabilitating their knee replacement, the majority of patients find this surgery challenging to recover from. As surgeons, we do our best to provide clear instructions, multimodal pain control, encouragement and support to our patients. Even my own patients, who I personally counsel in the office, and are then directed to this website, often end up falling behind the ideal rehabilitation schedule because of this mistake.

What is this mistake? The mistake is finding an excuse not to stretch your knee. Excuses fall into a couple categories. A common category relates to physical therapy. "My therapist couldn't get me in for 7 days following surgery." "The therapist was sick and canceled several visits." "I am only getting 2 PT sessions each week." "My physical therapist only told me to stretch for 5 seconds each day." Some of these relate to scheduling, and some are clearly misunderstanding/miscommunication. I can't imagine anybody honestly expecting a good result after surgery stretching for a few seconds each day, certainly not a legitimate physical therapist. Other reasons for falling behind relate to the normal inflammatory process we expect after surgery. "My knee felt (hot/tight/swollen, etc)." "I was letting it heal a bit and feel better before stressing it." A third category involves what exactly I mean by rehabilitation. "I have been doing a ton of walking." I have been using my stationary bike." "I have been going up and down stairs." Please, please, please don't get caught in this trap. I know that total knee rehabilitation is unpleasant. I know that it seems strange for me to ask you to stretch a painful, swollen joint. The problem is that any delay in stretching your new knee replacement will make subsequent gains more difficult. Each day that goes by allows the capsular tissues to contract a bit more, allows scar tissue and adhesions to grow and thicken. Take personal responsibility for your own rehabilitation. Begin stretching immediately. Check out this website. It was primarily designed to help you recover after surgery. I have articles and videos explaining how to rehabilitate your knee replacement properly. I explain how often to stretch and for how long. I provide a timeline for recovery. Do not wait for a physical therapist to tell you what to do. You already know what to do. Use them as a resource. Impress them with how much range of motion you regain between physical therapy sessions. Do not expect them to rehabilitate your knee for you. That will not provide an excellent outcome. While walking/biking/etc. are fine things to do, they are really not ideal exercises for regaining knee range of motion. Walking requires very little knee range of motion, and even a stationary bike will not optimize stretching. This is why I direct patients to long duration, passive stretching exercises. These exercises are the most efficient way to recover motion following knee replacement surgery. Expect your knee to swell. It will become discolored. It will feel tight. It will hurt. Do not let these symptoms hold you back from stretching. My rehabilitation recommendations are made expecting these symptoms to occur. Swelling, bruising, and pain are all a normal part of the recovery process. Do not wait for them to resolve before stretching. If you wait, you are likely to compromise your outcome.

7 Comments

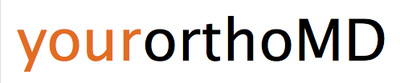

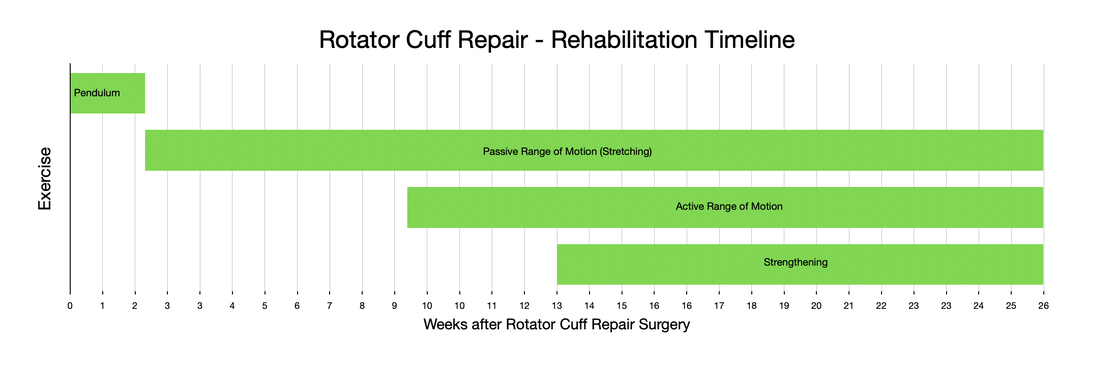

A stiff total knee replacement can be extremely frustrating for patients and surgeons. The best way to manage a still total knee is prevention. I have written many articles on this website focusing on how to rehabilitate your knee replacement effectively. Unfortunately, some patients will experience stiffness in spite of their best efforts. The management pathway I have outlined below is how I recommend dealing with this problem. For a bit more explanation, check out the video posted below. Rotator cuff repair is notoriously challenging to recover from. Not only is it generally painful, but it also requires adherence to a very specific protocol. Progressing too slowly results in prolonged stiffness and pain, while progressing too quickly risks the rotator cuff repair failing to heal. I recommend the following 4 steps. The first step begins at the time of surgery and ends 2 weeks after surgery. During this phase of rehabilitation I recommend minimizing any motion of your shoulder. Performing active finger, wrist, and elbow exercises is encouraged without limitation, but try to minimize any shoulder range of motion. Avoid any lifting, pushing, or pulling (even using only your hand) because it is really impossible to isolate your shoulder. You will be in an abduction sling, which allows the shoulder to rest, and takes tension off of the rotator cuff repair. To get dressed, and for hygiene, you will obviously have to temporarily remove the sling. Any motion of the shoulder during this stage must be passive only. The best way to accomplish this is via pendulum exercises. Step 2 involves intentional passive range of motion exercises. During this stage you still need to avoid any active range of motion. This is often difficult for patients. Following along with me in the accompanying video will very helpful. Stretching needs to continue on a daily basis from this point until you have full, symmetric range of motion with your other shoulder. Step 3 involves active range of motion. This is how we normally move around. Stretching should continue every day. No strengthening should occur yet. As you enter the final stage of rotator cuff rehabilitation, you will now add strengthening exercises. Strengthening should be done 2-3 times per week only. It is not appropriate to perform resistance exercises on a daily basis. The exercise stimulates the muscle to grow, it then needs a few days to actually grow. Most patients will continue to make progress with regard to range of motion, strength, endurance, and pain for an entire year following surgery. While the process is lengthy and unpleasant, careful adherence to this protocol will minimize the chance of ongoing stiffness and help prevent the rotator cuff from not healing. Many patients will need to continue stretching and strengthening for many months beyond what I have outlined above. This is normal, and anticipated. Continue stretching until you have achieved symmetry with your other shoulder. Continue strengthening until you are able to do all desired activities. most patients will report ongoing progress for an entire year following surgery.

As you navigate through this website, it should become quite clear how much I emphasize regaining range of motion as soon as possible after knee replacement surgery.

how-to-rehabilitate-your-total-knee-replacement.html another-way-to-stretch-your-knee-replacement.html the-best-total-knee-extension-stretch.html Ability to walk does not indicate adequate knee range of motion. One of the first questions I ask my patients at each follow-up visit after undergoing knee replacement surgery is: " How is your range of motion doing?" For some reason, a very common response is: "I am able to walk (x amount of ) distance." Clearly patients value ability to walk. And while I agree that walking is important, it is crucial to understand that regaining knee range of motion early after knee replacement is absolutely crucial to an excellent long-term outcome. Try a quick experiment. Take a few steps trying to keep one of your knees as straight as possible. See? It can be done. You will have a strange gait, but you can walk with almost no knee range of motion. Now walk normally while watching your knee move. Once again, very little range of motion is required to walk normally. Now sit in a chair and put your feet flat on the ground in front of you. Notice how your knees are bent to around 90 degrees. Now without bending your knees beyond 90 degrees, try to get up from a seated position without pushing off with your arms or thrusting your upper body foward to generate momentum. It is not possible. This is because your center of gravity is behind your feet. To stand up from a seated position, you simply must be able to bend beyond 90 degrees. It is essential to regain functional range of motion by 6 weeks after surgery. Remember, patients can only reliably regain knee range of motion for the first 6 weeks following knee replacement surgery. Beyond this point, scar tissue becomes too stiff and inflexible for simple stretching to be successful. When patients have not achieved an acceptable, functional range of motion by 6 weeks postoperatively, I recommend manipulation under anesthesia. My message is NOT - "Don't walk." Walking is important. It helps to prevent blood clots, it will help reduce swelling, and it is good for the lungs after surgery. Walking is just not sufficient to obtain an excellent result following knee replacement. As much as patients are focused on walking as a sign of recovery, I focus on regaining knee range of motion as the true indication of progress. To summarize: 1- Walking is important to patients and surgeons following knee replacement. 2- Walking does not require very much knee range of motion. 3- A patient's ability to walk after knee replacement does not necessarily indicate adequate knee rehabilitation. 4- The focus, particularly early after knee replacement (first 6 weeks), must be on regaining as much knee range of motion as possible. 5- The closer your knee range of motion is to normal following knee replacement, the more functional your knee will be for all activities (not just walking). 6- There is a limited time period (6 weeks) after a knee replacement for a patient to reliably regain range of motion. This is why I fixate so much on regaining motion as soon as possible after surgery. 7- Walking, comfort, confidence, strength, coordination, and endurance all will improve for months/years after knee replacement surgery. These factors all are improved when a patient has regained excellent range of motion. This means we should be patient with all of these parameters while focusing on early, consistent stretching to help ensure a good result.

Flexing the hip while also flexing the knee focuses most of the stretch on the knee joint. These first two videos demonstrate different ways to accomplish that. In the video below, notice how I am using my torso to generate the force needed to flex the knee. I then take up the slack created in the yoga strap with my arms. Also feel free to use your other leg to help generate flexion force as I demonstrate. The next video demonstrates how to use the strap to improve knee flexion while keeping the hip extended. This is done in the prone position. This will focus more of the stretch on the quadriceps muscle. I recommend stretching in each of these positions for the best result. Excellent knee function also requires full knee extension. The strap can help you achieve this as well. In the following video, I loop the strap over the knee to be stretched. I then place my other foot through a loop in each limb of the strap so that it does not touch the ground, but applies an extension force to the knee. The use of a yoga strap for knee replacement rehabilitation is certainly not mandatory, but simply provides another option to assist you. Always remember to use ice after stretching, hold the stretches for as long as possible, and relax your mind and muscles as much as possible during the stretch.

How much motion should you have at any given point after surgery? Of course, you should speak to your surgeon about the specifics of your case. However I'd like to provide some general guidance on this subject.

During knee replacement surgery, the knee will be reconstructed using a metal and plastic prosthesis, and the ligaments balanced. At the conclusion of the operation, the knee will be able to fully extend (straighten) and fully flex (bend back). After surgery, although initially pain will prevent full range of motion, scar tissue has not had a chance to form. Most patients are able to move from full extension (0 degrees) to 90 degrees (foot flat on floor while sitting in normal chair) within 24-48 hours. It is not uncommon for patients to lose a bit of motion around 7-10 days from surgery. This is a result of increased pain and swelling due to the inflammatory cascade. This inflammation peaks around 10 days from surgery. It is ok to go a bit easy on yourself during this time. Use plenty of ice and anti-inflammatory medication if it is allowed by your surgeon. But keep stretching. Do not allow yourself to lose full extension. This is crucial. By the first postoperative visit around 2 weeks from surgery I would like to see a minimum of 0-90 degrees of motion. By 6 weeks from surgery I would like to see 0-120 degrees minimum. Patients may gain an additional 5-10 degrees of deep flexion over the course of the first year following surgery if they've gotten to 120 degrees by 6 weeks. If these parameters are not met, other options are available. I begin asking patients to follow-up with me every other week or more to track their progress, to answer questions, and provide motivation and support. I understand that this process isn't always easy and is never fun. If inadequate range of motion isn't achieved by 6 weeks, I then recommend manipulation under anesthesia to break up scar tissue that has been allowed to form. This buys us some time and generally gets things back on track. total knee Total knee replacement surgery is an effective way to relieve arthritis pain when non-operative measures have failed. A substantial portion of the outcome, however, is based on adequately rehabilitating after surgery. The most important part of the rehabilitation program is regaining normal range of motion. This is easier said than done. At the time of a properly performed knee replacement surgery, the soft tissues are balanced and the range of motion should be full. That is: all the way straight, to all the way bent. This is something we test during surgery. Then the incision is closed and the healing process begins. Initially, there could be some swelling and acute surgical pain from the incision/surgical approach. Soon this acute pain subsides and stiffness begins. The stiffness is experienced by many patients as pain, especially when moving against the endpoint. In a prior posting I discussed the tissue planes that need to glide to allow proper motion. Each day that passes after knee replacement surgery, more healing occurs. This process can create connections, or adhesions, between these tissues. After about 6 weeks, enough scar tissue has formed, that most patients are unable to obtain more range of motion by stretching. In other words, at around 6 weeks from surgery no more progress with regard to range of motion is possible. The trouble is, in order to regain excellent function, adequate knee range of motion is necessary. Most patients are anxious to walk, ride a stationary bike, and are often quite focused on regaining strength. While these are fine things to do, and I certainly understand this desire, redirecting the focus to stretching appropriately remains my priority during the first 6 weeks postoperatively. Once range of motion is reestablished, all of these activities will be possible. Because we have a limited time to regain this range of motion this needs to be the priority early on. Thankfully these stretches are simple. Gently and progressively force the knee straight. And then gently and progressively force the knee bent. Simple! Except when it's not. Sometimes, and fortunately it is rare, a patient really struggles to regain range of motion after their total knee replacement. This can be a very frustrating situation for the patient and surgeon alike. I recommend stretching early, often, gently, but progressively. It is better to regain motion early than to attempt to catch up when stiffness is setting in. The simplest stretches are shown below:  knee extension stretch knee extension stretch This is one of the easiest stretches for extension. Place your ankle on a pillow. Relax your muscles to allow your knee to sag down. Then attempt to push the back of your knee down. This is a side view of my knee. It is important to note that my kneecap and toes are pointing straight up. This stretch can be held for minutes, gradually relax your muscles more and more, allow gravity to do the work. The longer the stretch the more the viscoelastic tissues will elongate.  avoid external rotation when doing knee extension stretch avoid external rotation when doing knee extension stretch This is the wrong way to stretch. This is a view of my knee from above. There is a natural tendency to externally rotate as your hips relax. Our goals are not being accomplished if this is allowed to happen. If you find this happening, simply place additional pillows or folded blankets along the outside of your foot and thigh to hold your toes and kneecap pointing up.  knee flexion stretch knee flexion stretch Now we are working on regaining flexion. In this example we are working on gaining flexion in my right knee (in the back ground of this photo). Here I have placed my left leg in front of my right ankle. I am using my left leg to help bend my stiff right knee more. This works best when done progressively over a period of minutes as opposed to seconds. Use your hamstrings in both legs to try to flex both knees further.  deeper knee flexion test using stepstool deeper knee flexion test using stepstool For deeper flexion than the previous stretch, this position utilizes a step-stool to provide deeper knee flexion. As shown, leaning forward and applying pressure with your hands can increase the stretch.  Deepest knee flexion stretch done in supine position Deepest knee flexion stretch done in supine position This is a stretch that can achieve extreme flexion. This time I am lying on my back. My knee is pointing up toward the ceiling. Flexing the hip relaxes the quadriceps. The hands are used to to pull the leg toward your body. The effect is increased hip and knee flexion. Please note: if you have a total hip replacement, be very careful with this position as it can produce significant hip flexion. These stretching positions should take care of 90% of total knee replacement patients. These stretches should be done everyday, ideally multiple times per day, with no days off. The longer the stretches can be held, the better. Remember to relax as much as possible while stretching and remember that a little pain is normal an expected. If no pain is encountered, I would recommend pushing a little bit harder. As always, if you have any specific questions about your particular case, discuss with your surgeon.

Occasionally we encounter a patient that has a very difficult time regaining motion. I have a few additional recommendations in these cases and will address that situation in an upcoming posting. I began playing ice hockey when I was 7 years old. When I was an orthopedic resident in New York City we formed a Hospital for Joint Diseases orthopedic hockey team. We had the unique opportunity to play outside in central park and also at Chelsea Piers with a view of the Hudson river and the New York skyline.

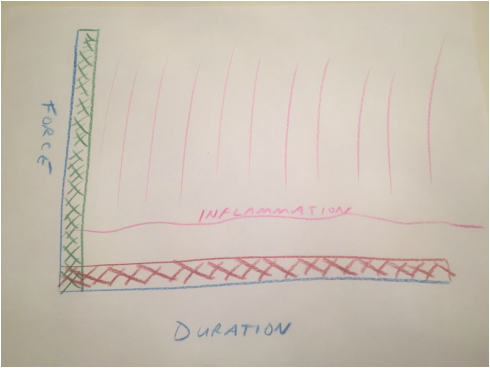

In spite of the violent reputation ice hockey has, I never personally sustained any significant injury. Until one evening around midnight (we had terrible ice times) when I was involved in a collision deep in my defensive zone. The back of my left shoulder made contact with the boards and I felt a zing of pain into the side of my arm. I immediately had difficulty raising my arm. Thankfully, it was toward the end of the game. I liberally applied ice when I got home, but when I woke up in the morning, I still couldn't actively raise my arm. I was fairly certain my injury was a rotator cuff contusion, and not a rotator cuff tear due to the mechanism of injury, and therefore would be self-limited. This proved to be correct, and by that afternoon, my active range of motion had returned, albeit with some pain. Confident my pain would improve as the contusion healed, I went about my normal daily activities for the next several weeks. I grew somewhat concerned however when the pain wasn't decreasing, but rather it was increasing. As a physician, working with world-renowned orthopedic surgeons who would be happy to assist me, I instead chose to ignore it. My life was too busy to deal with my shoulder. I could work, and for the most part I could compartmentalize the pain. Working at shoulder level or below was essentially normal and pain-free. But, if I forgot and suddenly reached for something, a knife-like jab brought my shoulder's issues front and center. After several months went by, I began to feel that my first choice of treatment (doing nothing) had failed. I finally examined my shoulder objectively and noted that although my strength was normal, I had lost some range of motion. More interestingly, I had lost not only active range of motion, but passive range of motion as well. At this instant I understood why my pain wasn't getting better. I had developed a frozen shoulder. Now everything made sense. At this point, I began my rehabilitation program. Everyday after work I applied ice to my shoulder for about 20 minutes. I purchased an ice machine to assist with this. I tried traditional stretching techniques, but was disappointed with the results. I was able to achieve intense pain, but absolutely no increase in range of motion. I actually felt I was getting worse. Frustration is an understatement. A possible treatment for a frozen shoulder that has been resistant to all nonoperative measures is a manipulation under anesthesia. The surgeon essentially forces the joint through a range of motion, tearing the tight tissues. This is something I clearly hoped to avoid. I recognized that biologic tissues are viscoelastic. I felt that based on this characteristic a stretch done gently, but for longer duration could be more effective. And so I began stretching differently. I measured the duration of stretch in minutes as opposed to seconds. I got to the painful endpoint and held it under tension for as long as I could tolerate it. Knowing that the longer I stretched the better it would be I increased the duration of my stretching to 30 minutes or more. Stretching hurts. I reminded myself that in spite of the pain I was experiencing, I was not creating damage. To maintain a stretch of this duration requires you to relax. The best position for me was to lay on the floor on my back and attempt to simultaneously touch my shoulder, elbow and wrist to the floor at the same time. I added some weight to my hand to increase the stretch and watched TV. I did this routine every day. At first I wasn't sure it was helping. But then I instinctively reached for something without thinking. Something that had previously caused a jolt of pain. And I felt no pain at all. This motivated me to add weight and time to the stretching program. Within a few more weeks my shoulder pain had resolved and I had regained normal range of motion. This method has made surgery for frozen shoulder very rare in my practice. When I first describe this technique to my patients, they seem incredulous. Most have already been through a course of physical therapy and are very frustrated. They presented to me to have an operation. But with very few exceptions (sometimes patients with diabetes have very resistant frozen shoulders), the vast majority of patients can avoid the operating room using this method. I will upload some pictures of how I recommend stretching in an upcoming post. Biologic tissues are viscoelastic. That means their stretchiness changes depending on how hard they are stretched. We can take advantage of this characteristic when we are rehabilitating a stiff joint. This becomes very important with certain medical problems. Specifically: total knee replacement and frozen shoulder. This concept is generally helpful in orthopedic rehabilitation and I take advantage of it whenever applicable. Think of silly putty. When slowly stretched it can be drawn out into a long strand, but when pulled aggressively it will snap and break in two. This is an extreme example of viscoelasticity. Your tissues are similar. While extreme force stretching can cause tissue to tear, this is generally far beyond any amount of stretching a patient can do, even with a physical therapist. A manipulation under anesthesia is a maneuver performed by a surgeon to rapidly regain motion in a particular joint that has become stiff. Tissues tear, and inflammation results. This is the most extreme example of a high force, low duration stretch. It is best to avoid this type of intervention if possible. It is preferable for a patient to spend the time necessary to recover joint range of motion using a long duration, low force stretch. It will result in less inflammation and less pain. Shoulders and knees commonly become stiff. Total knee rehabilitation requires stretching to regain range of motion after surgery. Stretching is required to speed up the recovery of a frozen shoulder. When attempting to regain range of motion patients are often told to stretch for 10-15 seconds and then relax. Over and over. Sometimes this is effective. Sometimes it is not. There is significant genetic variation with regard to tissue strength and inflammatory response, and significant psychological variation with regard to pain tolerance, and ability to relax while stretching. When a patient has trouble regaining range of motion I try to focus them on long duration, low force stretching. This tends to create less inflammation and is more likely to allow a patient to relax the muscles while stretching. Relaxing is very important because any muscle resistance will prevent gains in range of motion.  Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. This sketch depicts how I think about stretching. A high force, brief stretch is more likely to cause inflammation. A gentle prolonged stretch is less likely to create an inflammatory response. The "amount of stretch" or the total area under the curve depicted by the hash marks could be identical, but my experience suggests the long duration, low force stretching will give a superior result. How do I know this? When I was a resident, I developed a frozen shoulder and used long duration, low force stretching to cure myself. I have subsequently recommended this technique to countless patients who presented with frozen shoulders that had failed to improve after many weeks of standard physical therapy. Although occasionally surgical intervention was necessary, the vast majority progressed using this technique and never needed surgery. This technique has become my standard recommendation following total knee replacement and to rehabilitate a frozen shoulder, and has minimized the need for manipulation.

The difference between active and passive range of motion is easy for surgeons and physical therapists to understand, but is often unclear to patients.

Distinguishing between these two motions is crucial to properly rehabilitate certain surgeries, especially for a rotator cuff repair. Although I do my best to demonstrate each motion, and patients usually voice understanding, it is common for them to then demonstrate that they do not indeed understand. Active range of motion is what we normally do all day every day. Our body normally functions using a coordinated series of active motions. This motion is controlled by muscles. Muscles cross joints, which are where bones meet and move relative to each other. When a muscle contracts, a joint moves. This is active range of motion. Passive range of motion much less common in our normal daily activities. It requires a person to relax and allow their joint to be moved by an outside force. This force could be gravity, or another person (like a physical therapist), or a machine (like a stretching brace, or pulley). The rotator cuff is a commonly injured tendon. Repairing rotator cuff tears makes up a large part of my practice. I perform this surgery using an arthroscope, and it takes about an hour for me to repair the average rotator cuff tear. Patients usually go home the same day, wearing a special brace to protect the repair. This is where the hard work begins for the patient. Rehabilitating a repaired rotator cuff takes time, involves discomfort, and is not fun. It is also crucial to do it properly. Improperly rehabilitated rotator cuff repairs could result in problems. Inadequate stretching (passive range of motion) could cause stiffness. Too much active range of motion, too soon, could cause the repair to fail. I recommend thinking about rotator cuff rehabilitation as a sequence of 3 main phases:

It is very difficult to completely relax while someone, or something else moves your shoulder. Try to imagine your shoulder is paralyzed. Allow your arm to hang relaxed by your side. Then bend forward at your waist allowing your arm to swing away from your body under the influence of gravity . Keep bending at your waist as far as you can. At this point your arm will be hanging straight down, almost like you are trying to touch your toes or the floor in front of you. Now slowly stand up allowing your arm to gradually return to your side. Try to keep the arm completely relaxed throughout the entire motion. When you are standing upright again and your arm is at your side you are done. Congratulations. You just properly performed a basic passive range of motion exercise. In an upcoming post I will upload a video demonstrating this basic passive range of motion maneuver and a sequence of increasingly complex passive exercises. After this I will demonstrate active range of motion exercises. |

Dr. GorczynskiOrthopedic Surgeon focused on the entire patient, not just a single joint. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed