|

Some patients experience some mechanical sensations after knee replacement surgery. This is generally a normal consequence of the "hard bearing" components of the knee replacement prosthesis. Let me explain.

Cartilage is a coating of connective tissue that cushions the ends of the bones where the come together at a joint. This material, when healthy, is very slippery and provides some shock absorption to the bones. Healthy cartilage will allow a normal joint to move silently and painlessly. As the cartilage gradually wears out, it may fray, or pieces may break off. Now the joint surfaces are not perfectly smooth. The friction experienced with joint motion increases. As the cartilage layer thins out, its ability to cushion the bone ends also decreases. This all causes increased stress to the bones resulting in pain and stiffness. In response to the stress, the bone density often increases, bone spurs and/or areas of erosion may form, and the joint alignment may change. While these changes usually occur gradually over time, sometimes the progression may be rapid. X-rays will show joint space narrowing (loss of cartilage), sclerosis (increased bone density), osteophytes (bone spurs), cysts (areas of bone erosion). In addition to pain, a patient may experience grinding or crunching sensations from this increased friction and malalignment. These sensations are called crepitus. When we perform total knee replacement surgery, we precisely remove a few millimeters of bone from the end of the femur, tibia, and the undersurface of the patella. This is done in such a way that the prosthetic components will precisely fit the bones, re-align the mechanical axis of the leg, and balance the ligaments that support the joint. Because the prosthesis is metal and plastic, the bone ends no longer have any sensation where they come together. However, the joint surface is no longer soft cartilage, it is hard metal and plastic. Sometimes when these materials move relative to each other a patient may experience this as a clicking or other mechanical sensation. Early after knee replacement surgery, there will be blood and inflammatory fluid within the joint. When the knee is fully extended and the quadriceps are relaxed, the patella may "float" up, away from the femoral component where it normally rests. When the knee is then bent, or the quadriceps are contracted the patella will be pushed firmly down against the femoral component. This will feel like a click or a clunk. The click will not be painful, and will resolve as the fluid is reabsorbed from within the knee. Certain knee replacement models will substitute for the posterior cruciate ligament. This ligament prevents the tibia from moving posteriorly relative to the femoral component. This is accomplished using a polyethylene post on the tibial component. This post will engage against a bar on the femoral component when the knee is flexed and the tibia is pushed posteriorly. This engagement can feel like a click. Again, this is painless. The knee joint normally has a millimeter or two of laxity when stressed sideways. Pushing the tibia inward relative to the femur, and pushing the tibia outward relative to the femur tensions the lateral collateral and medial collateral ligament, respectively. Because there might be slight separation of the femoral and tibial components when applying these stress, a patient can experience a clicking sensation when the tension is removed and the prosthetic components re-engage. Using robotics during knee replacement surgery facilitates very accurate soft tissue balancing throughout the full knee range of motion. This accuracy of ligament balancing allows me to use a posterior cruciate retaining prosthesis (no post to engage) and minimizes side to side laxity. While some mechanical sensations can still occur (particularly with patellofemoral engagement early after surgery as described above), these sensations are minimized. These are the most common reasons a patient may feel some clicking in their knee following knee replacement surgery. When this occurs in the absence of pain, it is likely normal. If there is any question, I recommend you see your surgeon for an evaluation and reassurance.

0 Comments

While some patients have a very easy time rehabilitating their knee replacement, the majority of patients find this surgery challenging to recover from. As surgeons, we do our best to provide clear instructions, multimodal pain control, encouragement and support to our patients. Even my own patients, who I personally counsel in the office, and are then directed to this website, often end up falling behind the ideal rehabilitation schedule because of this mistake.

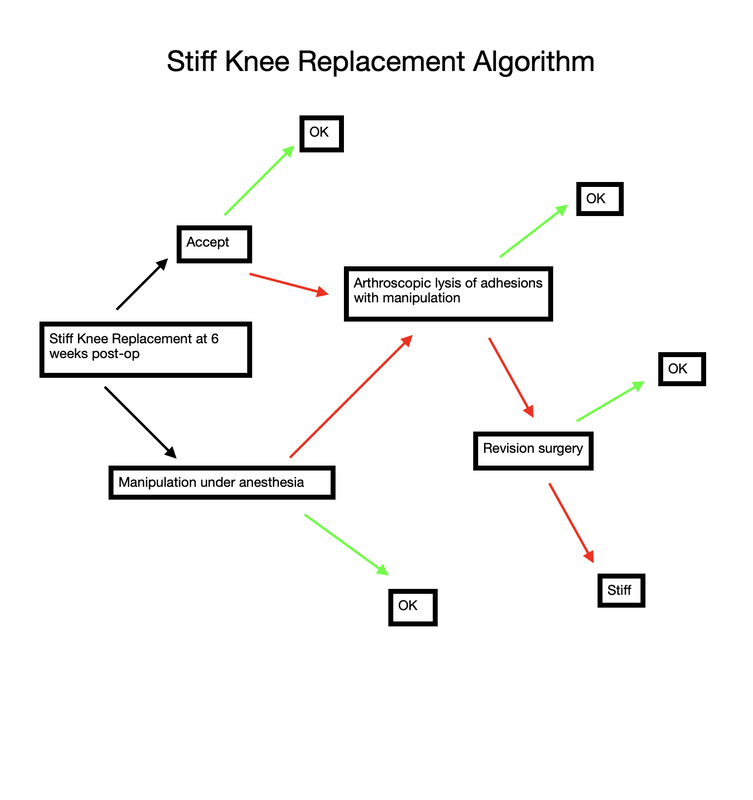

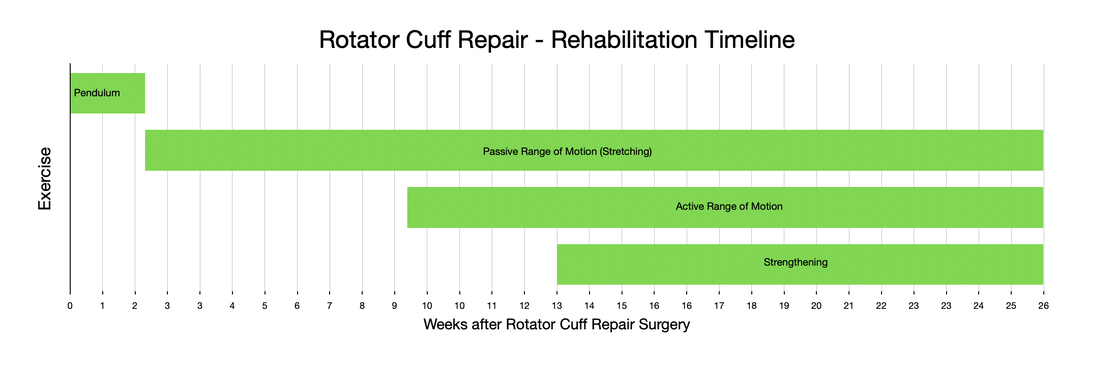

What is this mistake? The mistake is finding an excuse not to stretch your knee. Excuses fall into a couple categories. A common category relates to physical therapy. "My therapist couldn't get me in for 7 days following surgery." "The therapist was sick and canceled several visits." "I am only getting 2 PT sessions each week." "My physical therapist only told me to stretch for 5 seconds each day." Some of these relate to scheduling, and some are clearly misunderstanding/miscommunication. I can't imagine anybody honestly expecting a good result after surgery stretching for a few seconds each day, certainly not a legitimate physical therapist. Other reasons for falling behind relate to the normal inflammatory process we expect after surgery. "My knee felt (hot/tight/swollen, etc)." "I was letting it heal a bit and feel better before stressing it." A third category involves what exactly I mean by rehabilitation. "I have been doing a ton of walking." I have been using my stationary bike." "I have been going up and down stairs." Please, please, please don't get caught in this trap. I know that total knee rehabilitation is unpleasant. I know that it seems strange for me to ask you to stretch a painful, swollen joint. The problem is that any delay in stretching your new knee replacement will make subsequent gains more difficult. Each day that goes by allows the capsular tissues to contract a bit more, allows scar tissue and adhesions to grow and thicken. Take personal responsibility for your own rehabilitation. Begin stretching immediately. Check out this website. It was primarily designed to help you recover after surgery. I have articles and videos explaining how to rehabilitate your knee replacement properly. I explain how often to stretch and for how long. I provide a timeline for recovery. Do not wait for a physical therapist to tell you what to do. You already know what to do. Use them as a resource. Impress them with how much range of motion you regain between physical therapy sessions. Do not expect them to rehabilitate your knee for you. That will not provide an excellent outcome. While walking/biking/etc. are fine things to do, they are really not ideal exercises for regaining knee range of motion. Walking requires very little knee range of motion, and even a stationary bike will not optimize stretching. This is why I direct patients to long duration, passive stretching exercises. These exercises are the most efficient way to recover motion following knee replacement surgery. Expect your knee to swell. It will become discolored. It will feel tight. It will hurt. Do not let these symptoms hold you back from stretching. My rehabilitation recommendations are made expecting these symptoms to occur. Swelling, bruising, and pain are all a normal part of the recovery process. Do not wait for them to resolve before stretching. If you wait, you are likely to compromise your outcome. A stiff total knee replacement can be extremely frustrating for patients and surgeons. The best way to manage a still total knee is prevention. I have written many articles on this website focusing on how to rehabilitate your knee replacement effectively. Unfortunately, some patients will experience stiffness in spite of their best efforts. The management pathway I have outlined below is how I recommend dealing with this problem. For a bit more explanation, check out the video posted below. Rotator cuff repair is notoriously challenging to recover from. Not only is it generally painful, but it also requires adherence to a very specific protocol. Progressing too slowly results in prolonged stiffness and pain, while progressing too quickly risks the rotator cuff repair failing to heal. I recommend the following 4 steps. The first step begins at the time of surgery and ends 2 weeks after surgery. During this phase of rehabilitation I recommend minimizing any motion of your shoulder. Performing active finger, wrist, and elbow exercises is encouraged without limitation, but try to minimize any shoulder range of motion. Avoid any lifting, pushing, or pulling (even using only your hand) because it is really impossible to isolate your shoulder. You will be in an abduction sling, which allows the shoulder to rest, and takes tension off of the rotator cuff repair. To get dressed, and for hygiene, you will obviously have to temporarily remove the sling. Any motion of the shoulder during this stage must be passive only. The best way to accomplish this is via pendulum exercises. Step 2 involves intentional passive range of motion exercises. During this stage you still need to avoid any active range of motion. This is often difficult for patients. Following along with me in the accompanying video will very helpful. Stretching needs to continue on a daily basis from this point until you have full, symmetric range of motion with your other shoulder. Step 3 involves active range of motion. This is how we normally move around. Stretching should continue every day. No strengthening should occur yet. As you enter the final stage of rotator cuff rehabilitation, you will now add strengthening exercises. Strengthening should be done 2-3 times per week only. It is not appropriate to perform resistance exercises on a daily basis. The exercise stimulates the muscle to grow, it then needs a few days to actually grow. Most patients will continue to make progress with regard to range of motion, strength, endurance, and pain for an entire year following surgery. While the process is lengthy and unpleasant, careful adherence to this protocol will minimize the chance of ongoing stiffness and help prevent the rotator cuff from not healing. Many patients will need to continue stretching and strengthening for many months beyond what I have outlined above. This is normal, and anticipated. Continue stretching until you have achieved symmetry with your other shoulder. Continue strengthening until you are able to do all desired activities. most patients will report ongoing progress for an entire year following surgery.

As you navigate through this website, it should become quite clear how much I emphasize regaining range of motion as soon as possible after knee replacement surgery.

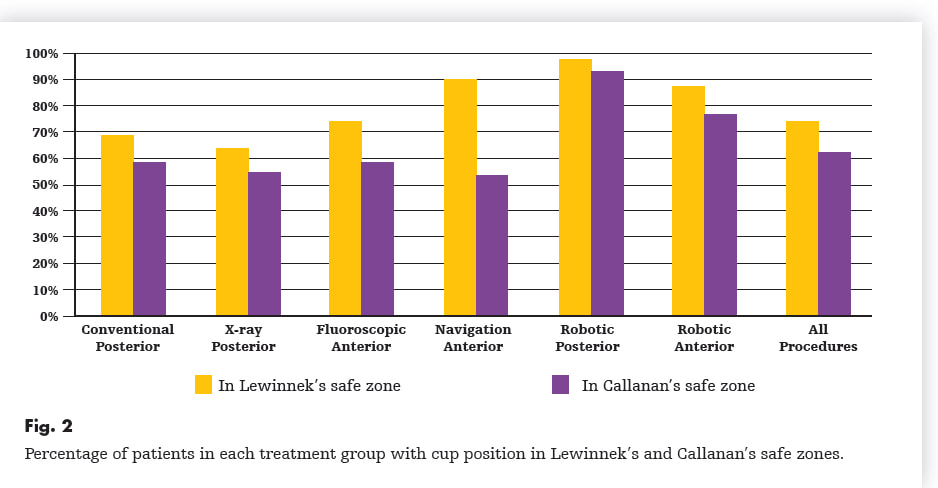

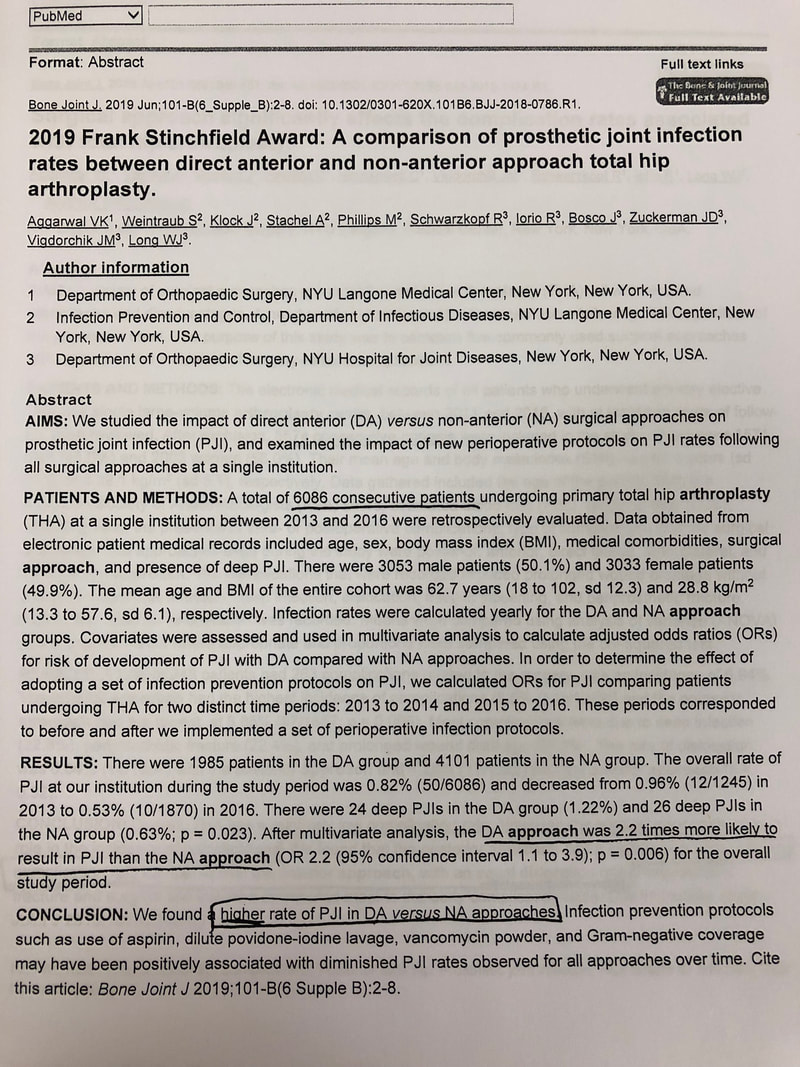

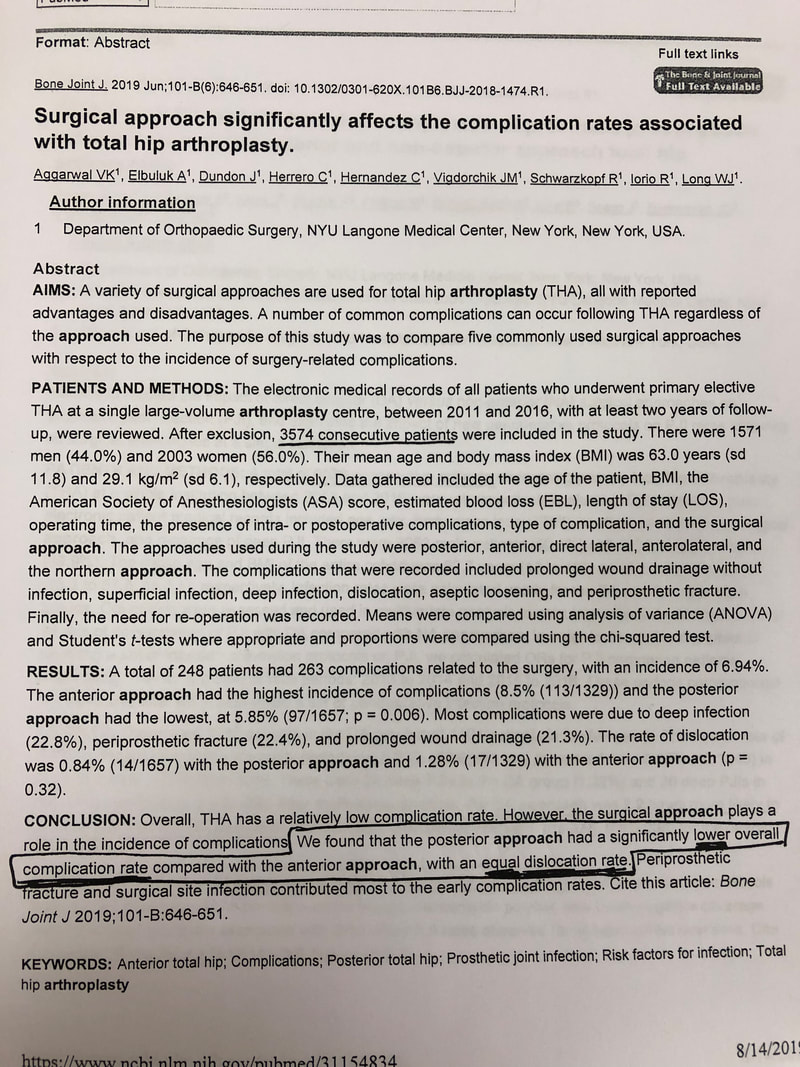

how-to-rehabilitate-your-total-knee-replacement.html another-way-to-stretch-your-knee-replacement.html the-best-total-knee-extension-stretch.html Ability to walk does not indicate adequate knee range of motion. One of the first questions I ask my patients at each follow-up visit after undergoing knee replacement surgery is: " How is your range of motion doing?" For some reason, a very common response is: "I am able to walk (x amount of ) distance." Clearly patients value ability to walk. And while I agree that walking is important, it is crucial to understand that regaining knee range of motion early after knee replacement is absolutely crucial to an excellent long-term outcome. Try a quick experiment. Take a few steps trying to keep one of your knees as straight as possible. See? It can be done. You will have a strange gait, but you can walk with almost no knee range of motion. Now walk normally while watching your knee move. Once again, very little range of motion is required to walk normally. Now sit in a chair and put your feet flat on the ground in front of you. Notice how your knees are bent to around 90 degrees. Now without bending your knees beyond 90 degrees, try to get up from a seated position without pushing off with your arms or thrusting your upper body foward to generate momentum. It is not possible. This is because your center of gravity is behind your feet. To stand up from a seated position, you simply must be able to bend beyond 90 degrees. It is essential to regain functional range of motion by 6 weeks after surgery. Remember, patients can only reliably regain knee range of motion for the first 6 weeks following knee replacement surgery. Beyond this point, scar tissue becomes too stiff and inflexible for simple stretching to be successful. When patients have not achieved an acceptable, functional range of motion by 6 weeks postoperatively, I recommend manipulation under anesthesia. My message is NOT - "Don't walk." Walking is important. It helps to prevent blood clots, it will help reduce swelling, and it is good for the lungs after surgery. Walking is just not sufficient to obtain an excellent result following knee replacement. As much as patients are focused on walking as a sign of recovery, I focus on regaining knee range of motion as the true indication of progress. To summarize: 1- Walking is important to patients and surgeons following knee replacement. 2- Walking does not require very much knee range of motion. 3- A patient's ability to walk after knee replacement does not necessarily indicate adequate knee rehabilitation. 4- The focus, particularly early after knee replacement (first 6 weeks), must be on regaining as much knee range of motion as possible. 5- The closer your knee range of motion is to normal following knee replacement, the more functional your knee will be for all activities (not just walking). 6- There is a limited time period (6 weeks) after a knee replacement for a patient to reliably regain range of motion. This is why I fixate so much on regaining motion as soon as possible after surgery. 7- Walking, comfort, confidence, strength, coordination, and endurance all will improve for months/years after knee replacement surgery. These factors all are improved when a patient has regained excellent range of motion. This means we should be patient with all of these parameters while focusing on early, consistent stretching to help ensure a good result. Over the years, surgeons have used a variety of surgical approaches to perform total hip replacement. Recently, there has been renewed excitement about the anterior approach. Much of this information is provided in the form of marketing/advertisement by surgeons working hard in competitive markets to grow their practice. Patients increasingly are led to believe that the anterior approach is a "different" operation. This is simply not true. The anterior approach is simply one of many approaches that can be used to perform hip replacement. I believe the data suggest the anterior approach is more about marketing than improved results. Total hip replacement is an excellent operation. It is very forgiving. When performed well, it is expected to provide dramatic improvement in pain, and quality of life for decades....regardless of approach. Why are there different approaches? Surgical approaches are anatomically safe routes between tissue planes that allow adequate exposure of deep anatomical structures. In the case of hip replacement surgery we must expose the acetabulum (hip socket) and femoral neck (top of the thigh bone). In some areas of the body there is really only one good approach. The hip, however, can be approached from the front, side, and back. Once down to bone, the operation is essentially identical, regardless of approach. Surgery, in general, has trade-offs. We need to cause controlled trauma to improve or fix something. As long as the improvement in disease outweighs the surgical trauma, the surgical procedure is worth doing. Obviously, the lower the surgical trauma the better for the patient. No surgery can be done without some trauma to the patient. In orthopedic surgery, the more accurately we can implant the joint replacement components, the better. Accuracy. With hip replacement surgery, we are replacing the patient's worn out ball and socket joint. It is crucial to place the socket (acetabular component) in a precise position. Think of the socket as a hemisphere. It is ideally aimed to be open to the side (horizontal inclination) and open to the front (anteverted). To accomplish this, the femur needs to be moved out of the way. If the cup is not ideally placed, it could allow the hip to dislocate or wear more rapidly than expected. For this reason, surgeons always look for ways to improve the position of the socket. Good surgeons are able to safely and precisely replace hips through any approach, however, most surgeons choose an approach based on their training and experience, and use it routinely. This repetition allows for greater reproducibility in outcomes. Traditionally, it was felt that the anterior approach allowed more accurate placement of the cup, with a potentially lower dislocation rate. The trade off was a higher rate of femur fracture because the anterior approach required more twisting of the femur during surgery. Recent studies (see below) bring this traditional tradeoff into question. I trained primarily with the posterior approach, and with a very low rate of dislocation using conventional (manual) alignment guides, I never felt the increased risk of intraoperative fracture warranted switching to the anterior approach. Robotic Total Hip Replacement...The most accurate total hip replacement. Now that I perform hip replacements robotically, there is absolutely no reason to consider changing approaches for accuracy. It turns out that the robotic posterior approach is the most accurate way to perform total hip replacement. But don't patients recover faster using the anterior approach? No. Most patients can bear full weight immediately and are able to go home the day after surgery with only mild pain regardless of approach. Any subtle differences, if any, patients experience between different approaches are gone within a few weeks. Risk vs. Benefit Two recent papers involving nearly 10,000 patients suggest there are potentially some significant disadvantages to the anterior approach relative to the posterior approach. The first paper found that hip replacements performed via the anterior approach became infected at over double the rate. The second paper found the posterior approach had a lower rate of complications and equal dislocation rate when compared to the anterior approach. The posterior approach appears to be the most accurate, and safest way to perform total hip replacement.

Flexing the hip while also flexing the knee focuses most of the stretch on the knee joint. These first two videos demonstrate different ways to accomplish that. In the video below, notice how I am using my torso to generate the force needed to flex the knee. I then take up the slack created in the yoga strap with my arms. Also feel free to use your other leg to help generate flexion force as I demonstrate. The next video demonstrates how to use the strap to improve knee flexion while keeping the hip extended. This is done in the prone position. This will focus more of the stretch on the quadriceps muscle. I recommend stretching in each of these positions for the best result. Excellent knee function also requires full knee extension. The strap can help you achieve this as well. In the following video, I loop the strap over the knee to be stretched. I then place my other foot through a loop in each limb of the strap so that it does not touch the ground, but applies an extension force to the knee. The use of a yoga strap for knee replacement rehabilitation is certainly not mandatory, but simply provides another option to assist you. Always remember to use ice after stretching, hold the stretches for as long as possible, and relax your mind and muscles as much as possible during the stretch.

A recent comment on another blog posting requested information on metal allergy/sensitivity. While this is a rare situation, I do have first-hand experience dealing with it. Common orthopedic materials include: cobalt, chrome, nickel, titanium, zirconium, polyethylene, and polymethylmethacrylate. Reactions have been reported to each of these materials. Thankfully these reactions are rare.

In the unusual case of a poorly functioning joint replacement, it is crucial to rule out other sources of dissatisfaction or failure prior to considering allergic reaction to the implant materials. More common issues include: infection, loosening, malalignment, instability, or wear. If a patient has a known sensitivity to any material, it is important to let your surgeon know this PRIOR to the intended surgery. It is reasonable to consider preoperative material testing in such situations. Once implanted, if sensitivity or allergy is felt to the the issue, revision surgery will be required. Depending on the particular material sensitivity, very specific implants will be required. I actually had to resort to using a custom zirconium revision total knee system in one case for a patient who was found to have intolerance to both nickel and titanium. Metal sensitivity is a controversial topic, however, and the literature continues to develop. It appears that after implantation of orthopedic devices, more people will test positive for sensitivity. In the case of positive metal sensitivity tests in association with a poorly functioning implant, it is unclear if the sensitivity is a cause of the implant difficulty or a result. Below, I have attached some recent abstracts highlighting some important points. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018 Jun 23;49:110-114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.06.011. [Epub ahead of print] Hypersensitivity to orthopaedic implant manifested as erythroderma: Timing of implant removal. Phedy P(1), Djaja YP(2), Boedijono DR(3), Wahyudi M(4), Silitonga J(5), Solichin I(6). Author information: (1)Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Fatmawati General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected]. (2)Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Fatmawati General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected]. (3)Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Fatmawati General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected]. (4)Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Fatmawati General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected]. (5)Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Fatmawati General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected]. (6)Rumah Sakit Orthopaedi Purwokerto, Purwokerto, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected]. INTRODUCTION: Incidence of hypersensitivity to orthopaedic implant, once estimated in less than 1% of population, recently has increased to 10%. Controversies about the timing of implant removal remain, especially due to the fact that implant hypersensitivity may be a contributing factor to implant failure. We present a case report and literature reviews to establish the decision making for the timing of implant removal in the presence of implant hypersensitivity. PRESENTATION OF CASE: Female, 42 years old with nonunion of mid-shaft tibia and fibula which was treated with ORIF with conventional SAE16 stainless steel plate and bone graft. A week after, she developed a generalized rash, which is later diagnosed as erythroderma, that relapsed despite adequate systemic corticosteroid. Poor healing of surgical site wound were marked. After the implant removal, the cutaneous condition improved and no relapse were found. DISCUSSION: Management of hypersensitivity to implants involved corticosteroid administration, removal or replacement of implants, or implants coating with polytetrafluoroethylene. Currently there are no specific guidelines regulating the management of implant allergy based on the timing of the onset, especially in fracture cases. The decision-making would be straightforward if union was already achieved. Otherwise, controversies would still occur. In this paper, we proposed an algorithm regarding the steps in managing metal allergy due to implant in fracture cases. CONCLUSION: Despite the concerns regarding implant survival in hypersensitivity cases, the decision whether the implant should be removed or replaced should be based on the time and condition of the fracture healing process. Copyright © 2018 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.06.011 PMCID: PMC6037004 PMID: 30005360 J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018 Jan-Mar;9(1):3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.10.003. Epub 2017 Oct 10. Metal hypersensitivity in total hip and knee arthroplasty: Current concepts. Akil S(1), Newman JM(1), Shah NV(1), Ahmed N(2), Deshmukh AJ(3), Maheshwari AV(1). Author information: (1)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, State University of New York (SUNY), Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA. (2)Saba University School of Medicine, Saba, Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands. (3)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, NYU Langone Medical Center, VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, New York, NY, USA. Metal hypersensitivity (MHS) is a rare complication of total joint arthroplasty that has been linked to prosthetic device failure when other potential causes have been ruled out. The purpose of this review was to conduct an analysis of existing literature in order to get a better understanding of the pathophysiology, presentation, diagnosis, and management of MHS. It has been described as a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to the metals comprising prosthetic implants, often nickel and cobalt-chromium. Patients suffering from this condition have reported periprosthetic joint pain and swelling as well as cutaneous, eczematous dermatitis. There is no standard for diagnosis MHS, but tests such as patch testing and lymphocyte transformation testing have demonstrated utility, among others. Treatment options that have demonstrated success include administration of steroids and revision surgery, in which the existing metal implant is replaced with one of less allergenic materials. Moreover, the definitive resolution of symptoms has most commonly required revision surgery with the use of different implants. However, more studies are needed in order to understand the complexity of this subject. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.10.003 PMCID: PMC5884053 [Available on 2019-01-01] PMID: 29628676 J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017 Oct;25(10):693-702. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00007. Allergic or Hypersensitivity Reactions to Orthopaedic Implants. Roberts TT(1), Haines CM, Uhl RL. Author information: (1)From the Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH (Dr. Roberts and Dr. Haines) and the Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, Albany Medical Center, Albany, NY (Dr. Uhl). Allergic or hypersensitivity reactions to orthopaedic implants can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Although 10% to 15% of the population exhibits cutaneous sensitivity to metals, deep-tissue reactions to metal implants are comparatively rare. Nevertheless, the link between cutaneous sensitivity and clinically relevant deep-tissue reactions is unclear. Most reactions to orthopaedic devices are type IV, or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. The most commonly implicated allergens are nickel, cobalt, and chromium; however, reactions to nonmetal compounds, such as polymethyl methacrylate, antibiotic spacers, and suture materials, have also been reported. Symptoms of hypersensitivity to implants are nonspecific and include pain, swelling, stiffness, and localized skin reactions. Following arthroplasty, internal fixation, or implantation of similarly allergenic devices, the persistence or early reappearance of inflammatory symptoms should raise suspicions for hypersensitivity. However, hypersensitivity is a diagnosis of exclusion. Infection, as well as aseptic loosening, particulate synovitis, instability, and other causes of failure must first be eliminated. DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00007 PMID: 28953084 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Rheumatol Ther. 2017 Jun;4(1):45-56. doi: 10.1007/s40744-017-0062-6. Epub 2017 Mar 31. Hypersensitivity to Orthopedic Implants: A Review of the Literature. Wawrzynski J(1), Gil JA(2), Goodman AD(3), Waryasz GR(3). Author information: (1)Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. (2)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. [email protected]. (3)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. Awareness of rare etiologies for implant failure is becoming increasingly important. In addition to the overall increase in joint arthroplasties, revision surgeries are projected to increase dramatically in the coming years, with volume increasing up to seven-fold between 2005 and 2030. The literature regarding the relationship between metal allergy and implant failure is controversial. It has proven difficult to determine whether sensitization is a cause or a consequence of implant failure. Testing patients with functional implants is not a clinically useful approach, as the rate of hypersensitivity is higher in implant recipients than in the general population, regardless of the status of the implant. As a result of the ineffectiveness of preoperative patch testing for predicting adverse outcomes, as well as the high cost of implementing such patch testing as standard procedure, most orthopedists and dermatologists agree that an alternative prosthesis should only be considered for patients with a history of allergy to a metal in the standard implant. In patients with a failed implant requiring revision surgery, hypersensitivity to an implant component should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Because a metal allergy to implant components is currently not commonly considered in the differential for joint failure in the orthopedic literature, there should be improved communication and collaboration between orthopedists and dermatologists when evaluating joint replacement patients with a presentation suggestive of allergy. DOI: 10.1007/s40744-017-0062-6 PMCID: PMC5443731 PMID: 28364382 HSS J. 2017 Feb;13(1):12-19. doi: 10.1007/s11420-016-9514-8. Epub 2016 Jul 22. Allergy in Total Knee Replacement. Does It Exist?: Review Article. Faschingbauer M(1)(2), Renner L(1)(3), Boettner F(1). Author information: (1)Hospital for Special Surgery, 535 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021 USA. (2)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Ulm, RKU, Oberer Eselsberg 45, 89081 Ulm, Germany. (3)Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Charite Universitaetsmedizin, Center for Musculosceletal Surgery, Chariteplatz 1, 10117 Berlin, Germany. BACKGROUND: There is little data on whether preexisting allergies to implant materials and bone cement have an impact on the outcome of TKA. QUESTIONS/PURPOSES: This review article analyzes the current literature to evaluate the prevalence and importance of metal and cement allergies for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. METHODS: A review of the literature was performed using the following search criteria: "knee," "arthroplasty," and "allergy" as well as "knee," "arthroplasty," and "hypersensitivity." RESULTS: One hundred sixteen articles were identified on PubMed, Seventy articles could be excluded by reviewing the title and abstract leaving 46 articles to be included for this review. The majority of the studies cited patch testing as the gold standard for screening and diagnosis of hypersensitivity following TKA. There is consensus that patients with self-reported allergies against metals or bone cement and positive patch test should be treated with hypoallergenic materials or cementless TKA. Treatment options include the following: coated titanium or cobalt-chromium implants, ceramic, or zirconium oxide implants. CONCLUSION: Allergies against implant materials and bone cement are rare. Patch testing is recommended for patients with self-reported allergies. The use of special implants is recommended for patients with a confirmed allergy. DOI: 10.1007/s11420-016-9514-8 PMCID: PMC5264571 PMID: 28167868 Conflict of interest statement: Martin Faschingbauer, MD reports other from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, during the conduct of the study. Lisa Renner, MD has declared that she has no conflict of interest. Friedrich Boettner, MD reports personal fees from Smith & Nephew, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Ortho Development, outside the work. Human/Animal Rights This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors. Informed Consent N/A Required Author Forms Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016 Dec 1;28(4):312-318. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.16.018. Availability of Total Knee Arthroplasty Implants for Metal Hypersensitivity Patients. Ajwani SH(1), Charalambous CP(1)(2)(3). Author information: (1)Department of Orthopaedics, Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Blackpool, UK. (2)School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, UK. (3)Institute of Inflammation and Repair, School of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. Purpose: To provide information on the type of "hypersensitivity-friendly" components available for primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the current market. Materials and Methods: Implant manufactures were identified using the 2013 National Joint Registries of the United Kingdom and Sweden and contacted to obtain information about the products they offer for patients with metal hypersensitivity. Results: Information on 23 TKA systems was provided by 13 implant manufacturers. Of these, 15 systems had options suitable for metal hypersensitivity patients. Two types of "hypersensitivity-friendly" components were identified: 10 implants were cobalt chrome prostheses with a "hypersensitivity-friendly" outer coating and 5 implants were made entirely from non-cobalt chrome alloys. Conclusions: The results of this study suggest that several hypersensitivity TKA options exist, some of which provide the same designs and surgical techniques as the conventional implants. The information in this study can guide TKA surgeons in making informed choices about implants and identifying implants that could be examined in future controlled studies comparing outcomes between "hypersensitivity-friendly" and conventional implants. DOI: 10.5792/ksrr.16.018 PMCID: PMC5134788 PMID: 27894179 J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016 Feb;24(2):106-12. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00290. Metal Hypersensitivity and Total Knee Arthroplasty. Lachiewicz PF(1), Watters TS, Jacobs JJ. Author information: (1)From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center (Dr. Lachiewicz and Dr. Watters) and the Durham Veterans Administration Medical Center (Dr. Lachiewicz), Durham, NC, and the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL (Dr. Jacobs). Metal hypersensitivity in patients with a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a controversial topic. The diagnosis is difficult, given the lack of robust clinical validation of the utility of cutaneous and in vitro testing. Metal hypersensitivity after TKA is quite rare and should be considered after eliminating other causes of pain and swelling, such as low-grade infection, instability, component loosening or malrotation, referred pain, and chronic regional pain syndrome. Anecdotal observations suggest that two clinical presentations of metal hypersensitivity may occur after TKA: dermatitis or a persistent painful synovitis of the knee. Patients may or may not have a history of intolerance to metal jewelry. Laboratory studies, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level, and knee joint aspiration, are usually negative. Cutaneous and in vitro testing have been reported to be positive, but the sensitivity and specificity of such testing has not been defined. Some reports suggest that, if metal hypersensitivity is suspected and nonsurgical measures have failed, then revision to components fabricated of titanium alloy or zirconium coating can be successful in relieving symptoms. Revision should be considered as a last resort, however, and patients should be informed that no evidence-based medicine is available to guide the management of these conditions, particularly for decisions regarding revision. Given the limitations of current testing methods, the widespread screening of patients for metal allergies before TKA is not warranted. DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00290 PMCID: PMC4726476 PMID: 26752739 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:137287. doi: 10.1155/2015/137287. Epub 2015 Mar 25. Biomaterial hypersensitivity: is it real? Supportive evidence and approach considerations for metal allergic patients following total knee arthroplasty. Mitchelson AJ(1), Wilson CJ(1), Mihalko WM(2), Grupp TM(3), Manning BT(1), Dennis DA(4), Goodman SB(5), Tzeng TH(1), Vasdev S(1), Saleh KJ(1). Author information: (1)Division of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Department of Surgery, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, P.O. Box 19679, Springfield, IL 62794-9679, USA. (2)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery & Biomedical Engineering, University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN 38017, USA. (3)Clinic for Orthopaedic Surgery, Campus Grosshadern, Ludwig Maximilians University, 80539 Munich, Germany ; Aesculap AG, Research & Development, 78532 Tuttlingen, Germany. (4)Colorado Joint Replacement, Denver, CO 80210, USA. (5)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Redwood City, CA 94063, USA. The prospect of biomaterial hypersensitivity developing in response to joint implant materials was first presented more than 30 years ago. Many studies have established probable causation between first-generation metal-on-metal hip implants and hypersensitivity reactions. In a limited patient population, implant failure may ultimately be related to metal hypersensitivity. The examination of hypersensitivity reactions in current-generation metal-on-metal knee implants is comparatively limited. The purpose of this study is to summarize all available literature regarding biomaterial hypersensitivity after total knee arthroplasty, elucidate overall trends about this topic in the current literature, and provide a foundation for clinical approach considerations when biomaterial hypersensitivity is suspected. DOI: 10.1155/2015/137287 PMCID: PMC4390183 PMID: 25883940 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Acta Orthop. 2015 Jun;86(3):378-83. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.999614. Epub 2015 Jan 13. The association between metal allergy, total knee arthroplasty, and revision: study based on the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Münch HJ(1), Jacobsen SS, Olesen JT, Menné T, Søballe K, Johansen JD, Thyssen JP. Author information: (1)National Allergy Research Centre, Department of Dermatology and Allergology , Gentofte University Hospital , Hellerup. BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: It is unclear whether delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions against implanted metals play a role in the etiopathogenesis of malfunctioning total knee arthroplasties. We therefore evaluated the association between metal allergy, defined as a positive patch test reaction to common metal allergens, and revision surgery in patients who underwent knee arthroplasty. PATIENTS AND METHODS: The nationwide Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register, including all knee-implanted patients and revisions in Denmark after 1997 (n = 46,407), was crosslinked with a contact allergy patch test database from the greater Copenhagen area (n = 27,020). RESULTS: 327 patients were registered in both databases. The prevalence of contact allergy to nickel, chromium, and cobalt was comparable in patients with and without revision surgery. However, in patients with 2 or more episodes of revision surgery, the prevalence of cobalt and chromium allergy was markedly higher. Metal allergy that was diagnosed before implant surgery appeared not to increase the risk of implant failure and revision surgery. INTERPRETATION: While we could not confirm that a positive patch test reaction to common metals is associated with complications and revision surgery after knee arthroplasty, metal allergy may be a contributor to the multifactorial pathogenesis of implant failure in some cases. In cases with multiple revisions, cobalt and chromium allergies appear to be more frequent. DOI: 10.3109/17453674.2014.999614 PMCID: PMC4443448 PMID: 25582229 [Indexed for MEDLINE] J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2014;24(1):37-44. Metal sensitivities among TJA patients with post-operative pain: indications for multi-metal LTT testing. Caicedo MS(1), Solver E(2), Coleman L(2), Hallab NJ(3). Author information: (1)Orthopedic Analysis, LLC, Chicago, IL 60612; Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL 60612. (2)Orthopedic Analysis, LLC, Chicago, IL 60612. (3)Orthopedic Analysis, LLC, Department of Immunology, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL 60612. Metal sensitivity testing is generally the diagnosis method of last resort for aseptic painful implants with elevated inflammatory responses. However, the relationship between implant-related pain and implant-debris-related metal sensitization remains incompletely understood. Although a sensitivity to nickel alone has been used as a general measure of metal allergy, it may lack the specificity to correlate sensitivity to specific implant metals and thus to select a biologically appropriate implant material. In this retrospective study, we report the incidence of pain and nickel sensitivity in patients with total joint arthroplasties (TJAs) referred for metal sensitivity testing (n=2018). We also correlated the degree of nickel hypersensitivity to implant pain levels (none, mild, moderate, and high, using a scale of 0-10) and the incidence of sensitivity to alternative implant metals in highly nickel-reactive subjects. Most patients (>79%) reported pain levels that were moderate to high regardless of implant age, whereas patients with severely painful TJAs had a statistically greater incidence of nickel sensitivity over the short-term post-operative period (≤4 years). Patients with moderate pain scores (4-7) and high pain scores (≥8) also exhibited significantly higher sensitivity to nickel compared to patients with no pain and no implant (controls) (p<0.05). Highly nickel-sensitive subjects (SI>8) also showed incidences of sensitization to alternative materials such as cobalt, chromium, or molybdenum (57%) or aluminum or vanadium alloy (52%). These data suggest that painful TJAs caused by metal sensitivity more likely occur relatively early in the post-operative period (≤4 years). The incidences of sensitivity to alternative implant metals in only a subset of nickel-reactive patients highlights the importance of testing for sensitization to all potential revision implant materials. PMID: 24941404 [Indexed for MEDLINE] J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2014;24(1):25-36. Evaluation and management of metal hypersensitivity in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Amini M(1), Mayes WH(1), Tzeng A(2), Tzeng TH(3), Saleh KJ(3), Mihalko WM(4). Author information: (1)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Biomedical Engineering, University of Tennessee Health Science Center; Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics, Memphis, TN. (2)Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Department of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. (3)Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield, IL. (4)Campbell Clinic Department of Orthopaedics & Biomedical Engineering University of Tennessee Health Science Center, TN, USA. Metal hypersensitivity has been an identified problem in orthopedics for nearly half a century, but its implications remain unclear. Establishing which total joint arthroplasty (TJA) candidates may do poorly with conventional implants and which patients would benefit from revision to an allergen-free implant remains challenging. Our systematic search of the MEDLINE database identified 52 articles for inclusion in our review. Case reports revealed that half of patients presented with pain and swelling, while only one-third presented with cutaneous symptoms. All patients were symptomatic within the first post-operative year; 90% were symptomatic within 3 months. Reports of patch testing revealed that patients with TJAs were positive for metal sensitivity more often than patients without TJAs (OR 1.3). Those with poorly functioning arthroplasties and those who had already had revisions tested positive more often than those with well-functioning TJAs (OR 1.7) and those without TJAs (OR 3.1). Lymphocyte transformation testing (LTT) shows promise in diagnosing metal allergy, and components of bone cement are also being recognized as potential allergens. Further work is necessary to delineate which patients should be tested for metal allergy and which patients would benefit from allergen-free implants. PMID: 24941403 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014 Aug;113(2):131-6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.05.012. Epub 2014 Jun 13. Metal hypersensitivity in total joint arthroplasty. Pinson ML(1), Coop CA(2), Webb CN(2). Author information: (1)Department of Medicine, Allergy/Immunology Division, Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, San Antonio, Texas. Electronic address: [email protected]. (2)Department of Medicine, Allergy/Immunology Division, Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, San Antonio, Texas. OBJECTIVE: To review the clinical manifestations, testing methods, and treatment options for hypersensitivity reactions to total joint arthroplasty procedures. DATA SOURCES: Studies were identified using MEDLINE and reference lists of key articles. STUDY SELECTIONS: Randomized controlled trials were selected when available. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of peer-reviewed literature were included, as were case series and observational studies of clinical interest. RESULTS: Total joint arthroplasty procedures are increasing, as are the hypersensitivity reactions to these implants. Evidence is not conclusive as to whether metal joint implants increase metal sensitivity or whether metal sensitivity leads to prosthesis failure. Currently, patch testing is still the most widely used method for determining metal hypersensitivity; however, there are no standardized commercial panels specific for total joint replacements available currently. In vitro testing has shown comparable results in some studies, but its use in the clinical setting may be limited by the cost and need for specialized laboratories. Hypersensitivity testing is generally recommended before surgery for patients with a reported history of metal sensitivity. In cases of metal hypersensitivity-related joint failure, surgical revision ultimately may be required. Knowledge about joint replacement hypersensitivity reactions becomes vital because the approach to the evaluation depends on appropriate testing to guide recommendations for future arthroplasty procedures. CONCLUSION: Evaluation of hypersensitivity reactions after total joint arthroplasty requires a systematic approach, including a careful history, targeted evaluation with skin testing, and in vitro studies. Copyright © 2014 American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.05.012 PMID: 24934108 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Int Orthop. 2014 Nov;38(11):2231-6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2367-1. Epub 2014 Jun 10. A prospective study concerning the relationship between metal allergy and post-operative pain following total hip and knee arthroplasty. Zeng Y(1), Feng W, Li J, Lu L, Ma C, Zeng J, Li F, Qi X, Fan Y. Author information: (1)Orthopadic Department of The First Affiliated Hospital, Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China, [email protected]. PURPOSE: A prospective study was conducted to detect whether a relationship exists between metal allergy and post-operative pain in total hip and knee arthroplasty patients. We postulated that to some extent a relationship does exist between them. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Patients who had undergone total hip and knee arthroplasty surgery because of hip and knee disease were included. The exclusion criteria were patients who were treated with immunosuppressor two weeks pre-operatively, skin conditions around the patch testing site, and other uncontrollable factors. Each patient agreed to patch testing for three days before surgery. Photographic images before patch testing, two and three days after patch testing were obtained to evaluate the final incidence of metal allergy. The patch tests contained 12 metal elements; chromium, cobalt, nickel, molybdenum, titanium, aluminium, vanadium, iron, manganese, tin, zirconium, and copper. Two independent observers evaluated the images. The results were divided into a non-metal allergy group and a metal allergy group. Pre-operative and postoperative VAS score, lymphocyte transforming test, and X-rays were collected to detect the relationship between metal allergy and post-operative pain following total hip and knee arthroplasty. RESULTS: There were 96 patients who underwent pre-operative patch testing. The overall metal allergy rate was 51.1% (49/96) in our study. Nickel, cobalt, manganese, and tin were the most common allergic metal elements in our study. Nine inappropriate cases were excluded, and 87 patients were finally included in our study. There were 36 metal allergy and 26 non-metal allergy patients in the THA group, while 11 metal allergy and 14 non-metal allergy patients were found in the TKA group. We found no relationship existed between metal allergy and post-surgery pain in total hip and knee arthroplasty. CONCLUSION: Pain caused by metal allergy usually presents as persistent and recurrent pain. The white cell count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and postoperative radiographs were not affected. Currently, patch testing and lymphocyte transforming tests are used for metal allergy diagnosis. We deemed that a relationship between post-surgery pain and metal allergy in total hip and knee patients may exist to some extent. Larger samples and longer follow-up time are essential for further study. DOI: 10.1007/s00264-014-2367-1 PMID: 24910214 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012 Sep;25(4):463-9. doi: 10.2478/S13382-012-0029-3. Epub 2012 Dec 3. Allergy to orthopedic metal implants - a prospective study. Kręcisz B(1), Kieć-Świerczyńska M, Chomiczewska-Skóra D. Author information: (1)Center of Occupational Allergy and Environmental Health, Nofer Institute of Occupational Medicine, Łódź, Poland. [email protected] OBJECTIVES: Evaluation of the allergenic properties of the metal knee or hip joint implants 24 months post surgery and assessment of the relation between allergy to metals and metal implants failure. MATERIALS AND METHODS: The study was conducted in two stages. Stage I (pre-implantation) - 60 patients scheduled for arthroplasty surgery. Personal interview, dermatological examination and patch testing with 0.5% potassium dichromate, 1.0% cobalt chloride, 5.0% nickel sulfate, 2.0% copper sulfate, 2.0% palladium chloride, 100% aluminum, 1% vanadium chloride, 5% vanadium, 10% titanium oxide, 5% molybdenum and 1% ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate were performed. Stage II (post-surgery) - 48 subjects participated in the same procedures as those conducted in Stage I. RESULTS: Stage I - symptoms of "metal dermatitis" were found in 21.7% of the subjects: 27.9% of the females, 5.9% of the males. Positive patch test results were found in 21.7% of the participants, namely to: nickel (20.0%); palladium (13.3%); cobalt (10.0%); and chromium (5.9%). The allergy to metals was confirmed by patch testing in 84.6% of the subjects with a history of metal dermatitis. Stage II - 10.4% of the participants complained about implant intolerance, 4.2% of the examined persons reported skin lesions. Contact allergy to metals was found in 25.0% of the patients: nickel 20.8%, palladium 10.4%, cobalt 16.7%, chromium 8.3%, vanadium 2.1% Positive post-surgery patch tests results were observed in 10.4% of the patients. The statistical analysis of the pre- and post-surgery patch tests results showed that chromium and cobalt can be allergenic in implants. CONCLUSIONS: Metal orthopedic implants may be the primary cause of allergies. that may lead to implant failure. Patch tests screening should be obligatory prior to providing implants to patients reporting symptoms of metal dermatitis. People with confirmed allergies to metals should be provided with implants free from allergenic metals. DOI: 10.2478/S13382-012-0029-3 PMID: 23212287 [Indexed for MEDLINE] J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Nov;94(11 Suppl A):14-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B11.30680. The Hip Society: algorithmic approach to diagnosis and management of metal-on-metal arthroplasty. Lombardi AV Jr(1), Barrack RL, Berend KR, Cuckler JM, Jacobs JJ, Mont MA, Schmalzried TP. Author information: (1)The Ohio State University, Department of Orthopaedics and Department of Biomedical Engineering, 7277 Smith's Mill Road, Suite 200, New Albany, Ohio 43054, USA. [email protected] Since 1996 more than one million metal-on-metal articulations have been implanted worldwide. Adverse reactions to metal debris are escalating. Here we present an algorithmic approach to patient management. The general approach to all arthroplasty patients returning for follow-up begins with a detailed history, querying for pain, discomfort or compromise of function. Symptomatic patients should be evaluated for intra-articular and extra-articular causes of pain. In large head MoM arthroplasty, aseptic loosening may be the source of pain and is frequently difficult to diagnose. Sepsis should be ruled out as a source of pain. Plain radiographs are evaluated to rule out loosening and osteolysis, and assess component position. Laboratory evaluation commences with erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, which may be elevated. Serum metal ions should be assessed by an approved facility. Aspiration, with manual cell count and culture/sensitivity should be performed, with cloudy to creamy fluid with predominance of monocytes often indicative of failure. Imaging should include ultrasound or metal artifact reduction sequence MRI, specifically evaluating for fluid collections and/or masses about the hip. If adverse reaction to metal debris is suspected then revision to metal or ceramic-on-polyethylene is indicated and can be successful. Delay may be associated with extensive soft-tissue damage and hence poor clinical outcome. DOI: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B11.30680 PMID: 23118373 [Indexed for MEDLINE] J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Aug;94(8):1126-34. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B8.28135. Metal hypersensitivity testing in patients undergoing joint replacement: a systematic review. Granchi D(1), Cenni E, Giunti A, Baldini N. Author information: (1)Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute, Laboratory for Orthopaedic Pathophysiology and Regenerative Medicine, Via di Barbiano 1/10, 40136 Bologna, Italy. [email protected] We report a systematic review and meta-analysis of the peer-reviewed literature focusing on metal sensitivity testing in patients undergoing total joint replacement (TJR). Our purpose was to assess the risk of developing metal hypersensitivity post-operatively and its relationship with outcome and to investigate the advantages of performing hypersensitivity testing. We undertook a comprehensive search of the citations quoted in PubMed and EMBASE: 22 articles (comprising 3634 patients) met the inclusion criteria. The frequency of positive tests increased after TJR, especially in patients with implant failure or a metal-on-metal coupling. The probability of developing a metal allergy was higher post-operatively (odds ratio (OR) 1.52 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.06 to 2.31)), and the risk was further increased when failed implants were compared with stable TJRs (OR 2.76 (95% CI 1.14 to 6.70)). Hypersensitivity testing was not able to discriminate between stable and failed TJRs, as its predictive value was not statistically proven. However, it is generally thought that hypersensitivity testing should be performed in patients with a history of metal allergy and in failed TJRs, especially with metal-on-metal implants and when the cause of the loosening is doubtful. DOI: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B8.28135 PMID: 22844057 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Knee. 2012 Mar;19(2):144-7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.01.001. Epub 2011 Feb 2. Metal hypersensitivity in total knee arthroplasty: revision surgery using a ceramic femoral component - a case report. Bergschmidt P(1), Bader R, Mittelmeier W. Author information: (1)Department of Orthopaedics, University of Rostock, Germany. [email protected] We present a case involving the revision of a total knee arthroplasty with a metal femoral component using a ceramic implant due to metal hypersensitivity. A 58-year-old female patient underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with a standard metal bicondylar knee system. She suffered from persistent pain and strong limitations in her range of motion (ROM) associated with flexion during the early postoperative period. Arthroscopic arthrolysis of the knee joint and intensive active and passive physical treatment, in combination with a cortisone regime, temporarily increased the ROM and reduced pain. No signs of low grade infection or other causes of implant failure were evident. Histology of synovial tissue revealed lymphoplasmacellular fibrinous tissue, consistent with a type IV allergic reaction. Allergometry (skin reaction) revealed type IV hypersensitivity against nickel-II-sulfate and palladium chloride. Revision surgery of the metal components was performed with a cemented ceramic femoral component (same bicondylar design) and a cemented titanium alloy tibial component. Postoperative evaluations were performed 10days, and 3 and 12months after the revision surgery. There was an increased ROM in flexion to 90° at the 12month follow-up. No swelling or effusion was observed at all clinical examinations after the revision surgery. No pain at rest and moderate walking pain were evident. The presented case demonstrates that ceramic implants are a promising solution for patients suffering from hypersensitivity to metal ions in total knee arthroplasty. Copyright © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.01.001 PMID: 21292491 [Indexed for MEDLINE] Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2006;19(3):178-80. Allergy to metals as a cause of orthopedic implant failure. Krecisz B(1), Kieć-Swierczyńska M, Bakowicz-Mitura K. Author information: (1)Department of Occupational Diseases, Nofer Institute of Occupational Medicine, Lódź, Poland. [email protected] BACKGROUND: A constantly growing social demand for orthopedic implants has been observed in Poland. It is estimated that about 5% of patients experience post-operation complications. It is suspected that in this group of patients an allergic reaction contributes to rejection of metal implants. MATERIALS AND METHODS: The aim of our study was to assess contact allergy to metals in 14 people (9 women and 5 men) suffering from poor implant tolerance. In some of them, recurrent skin eruptions, generalized or nearby implants, have occurred and in 3 patients skin fistula was observed. These complaints appeared one year after operation. The patients underwent patch tests with allergens from the Chemotechnique Diagnostics (Malmö, Sweden), including nickel, chromium, cobalt, palladium, copper, aluminum. In addition, allergens, such as titanium, vanadium and molybdenum prepared by chemical laboratory in the Nofer Institute of Occupational Medicine, Lódiź, Poland, were introduced. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: Of the 14 patients, 8 persons (5 women and 3 men) were sensitized to at least one metal, mostly to nickel (7/14) and chromium (6/14). Of the 8 sensitized patients, 3 were reoperated. Owing to the exchange of prosthesis the complaints subsided, including healing up skin fibulas. These facts weight in favor of the primeval sensitizing effect of metal prosthesis and the relation between allergy and clinical symptoms of poor tolerance to orthopedic implants. PMID: 17252668 [Indexed for MEDLINE] With over a million knee arthroscopic surgeries performed in the United States every year, at this point just about everyone has heard about someone having their knee "scoped." This is a quick, low risk procedure that provides relief in the majority of patients. Why then am I finding myself spending increasing amounts of time talking patients out of this procedure? It is important to understand what can be done to a knee with the arthroscope.

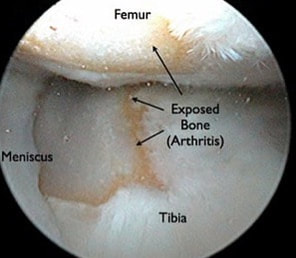

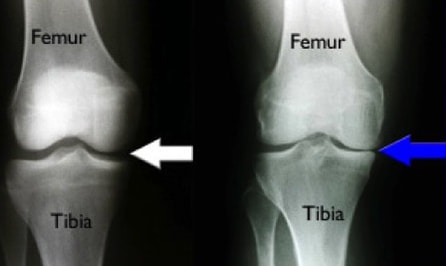

It is crucial to understand one very important thing that can NOT be done with the arthroscope. We can not "remove," "clean-up," or otherwise fix arthritis. Arthritis involves the permanent loss of articular cartilage. This is the cartilage cushion that coats the bone ends as they meet within the joint. Once articular cartilage is gone, it is gone. The solution when symptoms are unacceptable is joint replacement. Not arthroscopy. So what does all of this have to do with the meniscus? Let me describe an extremely common situation I encounter in my practice. A patient presents to my office with chief complaint of "torn meniscus." They have already had an MRI scan done. Indeed, contained within this report there is reference to a "meniscal tear." There is often reference to some degree of chondromalacia, articular cartilage degeneration, exposed bone, bone marrow edema, or subchondral cysts. All of these terms are essentially saying: "osteoarthritis." I always look at these MRI images with patients. I describe all of these pertinent findings. I explain that when there is arthritis in the same knee compartment as a meniscal tear, the pain is most likely due to the arthritis. Even if the meniscus is contributing to the pain, removing it will in no way guarantee pain relief. Many times at this point I am then asked, "so can you clean up the meniscal tear?" It is this fixation on the meniscus that I am attempting to correct. It is crucial to understand that surgically treating a degenerative meniscal tear in an arthritic knee is unpredictable at best. A patient anticipating a miraculous cure can easily be disappointed with the result. One of the most important studies we do is standing knee x-rays. Bone partially blocks x-rays whereas cartilage does not. When standing, a healthy knee has a clear separation between the femur and tibia. This separation is known as the joint space. It shows us how much articular cartilage there is. This joint space is not the meniscus, it is articular cartilage. When this joint space becomes narrowed, we know there is some arthritis. The term "bone-on-bone" arthritis refers to the complete loss of joint space on a standing knee x-ray. This is what severe arthritis looks like.

A good candidate for meniscal surgery is a patient who has been experiencing ongoing pain, swelling, and who has tenderness to palpation over the involved joint line. This is usually made worse by crouching or twisting. Standing x-rays should not reveal much, if any joint space narrowing. An MRI scan should not show articular cartilage loss or bone marrow edema. In this situation, a knee arthroscopy is a low-risk, high-reward procedure. ,It has been customary for decades to use a pneumatic tourniquet during total knee replacement surgery. Inflation of the tourniquet initiated the very first total knee replacement I saw as a medical student, every total knee replacement I did during training, and nearly every total knee I performed while in practice.

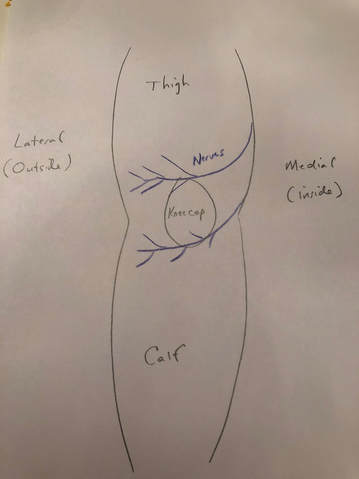

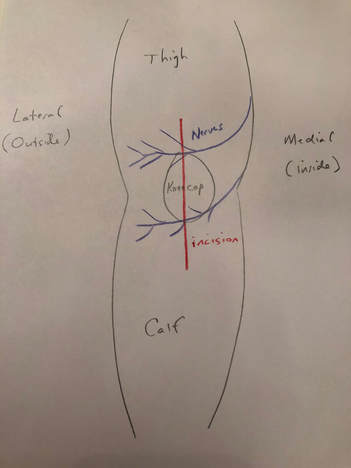

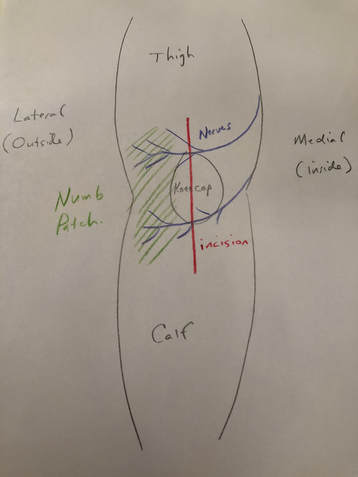

The perceived benefit of tourniquet use was reduced blood loss and better visualization of the tissues during surgery. Total blood loss is defined as any blood loss during surgery, PLUS any postoperative blood loss into dressings or drains, or into the joint or leg. This can be quantified by comparing pre-operative hematocrit (blood count) with the lowest post-operative hematocrit. A recent paper suggests that total blood loss paradoxically INCREASES if a tourniquet is used during surgery. A variety of additional recent papers suggest the same thing. How can this be? Reactive Hyperemia (a period of increased blood flow after tourniquet release) While a tourniquet is inflated, arterial inflow to the limb is stopped. This is nice for the surgeon during the operation as visualization is easier, and no time needs to be spent controlling bleeding. Many surgeons release the tourniquet at the conclusion of the operation, but prior to closing the incision. This allows any bleeding to be controlled. This was what I always did, because I wanted to be sure all active bleeding was stopped prior to wound closure. I hoped to minimize any post-operative bleeding as well as total tourniquet time. Some surgeons do not choose to do this but maintain the tourniquet until a compressive dressing has been applied. The problem is that after the period of ischemia (no blood flow), the tissues demand more blood supply, and the blood flow to the limb increases for a period of time after surgery. This is known as reactive hyperemia. As a result, sometimes after surgery, blood will collect in the knee, accumulate in the dressing, and/or be removed in a drain. This can be uncomfortable for patients and it increases total blood loss. There are other downsides of tourniquet use. Intravenous antibiotics are given just prior to initiation of surgery to help reduce the chance of infection. While this medication is infused prior to tourniquet inflation, once the tourniquet is inflated, blood is no longer circulating and thus, antibiotic medication is not circulating either. Ischemic tissues will become cold making cellular activity and enzymes less effective. Ischemia is stressful to the tissues. This increases inflammation. The tourniquet applies significant pressure to the soft tissues. This can contribute to pain and bruising of the thigh postoperatively. Because the tourniquet stops blood flow, it also increases the chance of blood clot formation. I encountered occasional cases where the tourniquet didn't work well. This can happen if a patient has high blood pressure, their arteries are calcified, or if their thigh is large. In these cases the tourniquet restricts venous outflow but allows arterial inflow since arterial pressure is higher. We refer to this as a "venous tourniquet." When this happened I would drop the tourniquet and carry on as usual. The operation went fine. A bit more time was needed to stop bleeding during surgery, but the results were no different than when using a tourniquet. Based on this, the theoretical negative tourniquet effects, and the recent papers suggesting tourniquet paradoxically increases total blood loss, I decided to stop inflating the tourniquet for total knee replacements. I spend a few more minutes controlling bleeding during the surgical approach. Once this initial bleeding is controlled, there is minimal ongoing blood loss for the remainder of the case. This is analogous to total hip replacement where tourniquet use is impossible due to the location of surgery. Visualization is excellent. The bone ends are irrigated using pulsatile lavage, and dried as usual prior to implanting the knee replacement components. By this stage of the operation, the knee looks basically the same as it does when using a tourniquet. Prior to closure, all bleeding has stopped. No drain is necessary. Tranexamic acid is a medication that helps reduce blood loss, and we use this in most patients. I have been very pleased with the results since I have discontinued routine use of the tourniquet for total knee replacement surgery. I found patients are more comfortable and there is noticeably less swelling and bruising. Knee range of motion has been returning quicker. We are continually working on process improvement to allow patients to return to their normal life as rapidly as possible. This begins with preoperative education, continues with a multimodality pain management plan, a 3-dimensionally planned, robotically assisted joint replacement operation, and early mobilization. My experience is that discontinuing use of the pneumatic tourniquet is yet another step to help patients recover quicker. Nearly every patient will experience some degree of permanent numbness on the lateral (outside) side of the knee after knee replacement surgery. This is anticipated. It is so common, most surgeons do not discuss this with their patients prior to surgery. It is not a complication, but a necessary side-effect of achieving a safe exposure to perform knee replacement surgery.

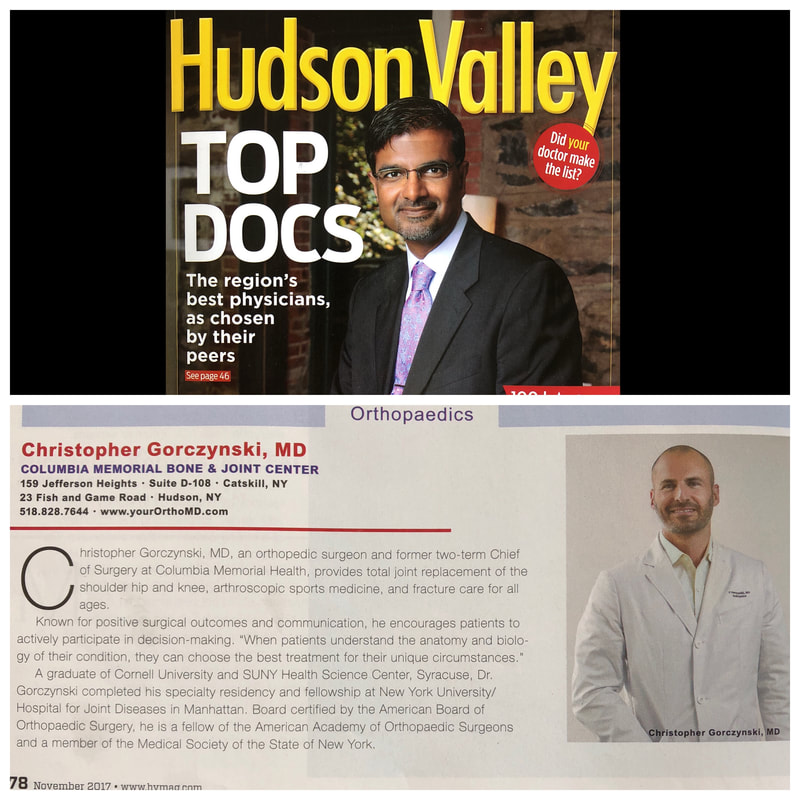

What is going on? There are cutaneous (skin) nerves that cross the front of the knee from the inside (medial) to the outside (lateral). A knee replacement incision is made longitudinally over the front (anterior) of the knee. These small nerves must be cut to allow deeper exposure. Other than a numb patch on the outside of the knee, there is generally no other negative effect. Once rehabilitated, patients rarely even mention this finding. Most are just thrilled their arthritic pain is gone and they are back to their desired activities again. I am thrilled to announce my selection as a "top doc" in orthopedic surgery by Hudson Valley Magazine for 2017!

The majority of my orthopedic surgical practice consists of arthroscopic surgery and total joint replacement. During surgery, I use a robotic system that allows me to perform knee and hip joint replacements with extreme precision. Total and reverse total shoulder replacements are also common procedures for me. Shoulder and knee arthroscopy allows minimally invasive treatment of rotator cuff tears, shoulder instability, cruciate ligament and meniscal pathology. My collaborative approach allows customization of treatment to meet my patients personal goals. I make a great effort to educate and answer all questions so an individual patient's treatment makes sense to them. I am very fortunate to be able to solve orthopedic problems for people, and to improve their quality of life. Public recognition like this is a great honor to me. The future is here!

We are thrilled to announce that we are establishing a robotically assisted total joint replacement program here in Hudson, New York. We will be using the Stryker Mako system for partial knee replacements, total knee replacements, and total hip replacements. What is the big deal? Accuracy. Patients and surgeons are very fortunate in that total joint replacement is reproducible, predictable and forgiving. That does not mean it is perfect. While patients routinely report dramatic pain relief once rehabilitated, we as surgeons are thrilled when they report that their new joint feels "normal." This occurs less often than anyone would like. During surgery, we use alignment guides designed to produce certain angles, or remove a particular amount of bone. These guides have been the same for decades. Good surgeons will achieve consistent results, but even the very best surgeons will admit that there is more variability than anyone would like. This can occur for a variety of reasons, but it is impossible to completely avoid. Using a robotic arm during surgery, we can implant joint prostheses within a millimeter and a degree of the intended plan. Every time. No surgeon, anywhere, can do this using manual tools. Before you begin imagining a robotic arm like those seen in vehicle assembly, let me explain how the Styker Mako robotic arm works. Preoperatively, the patient undergoes a CT scan. The surgeon then plans the surgery virtually on the computer, determining the intended alignment and position of the prosthesis. In the operating room, the surgeon makes the surgical approach and then uses a probe to orient the robotic software to the position of the patients bones. During preparation of the bone, the robotic arm prevents anything but the exact plan from being executed. It does this passively. At no point can the robot move itself. The surgeon positions the tools and prostheses and once perfectly aligned, the robot locks the tool into this perfect position. The handpiece, which is operated by the surgeon, will not be activated until it is perfectly aligned and in a safe position. The surgeon then activates the tool, or manually impacts the prosthesis depending on the step in the procedure. The surgeon gets real-time information regarding implant position as it is happening. From the surgeon's perspective, this information is invaluable! We can adjust our plan intraoperatively if needed. We can execute our plan perfectly, every time. During knee replacement, we can balance ligaments degree by degree. During hip replacement, we can optimize acetabular (socket) placement, leg length, and offset. When dealing with complex biological systems, there will always be factors beyond our control. Robotic total joint replacement is an amazing tool, which gives us tighter control over prosthetic implantation and soft tissue balance. This will improve the function and longevity of implants for patients. Much of this website is directed toward proper rehabilitation after joint replacement. While prosthetic alignment and soft tissue balance will be improved using the Mako robot, appropriate rehabilitation will always be crucial to maximizing outcomes. Total knee replacement has become a very common elective surgery, and patients are often amazed at how quickly they can get back to "normal" life after surgery. Within hours of their surgery, my patients are often able to begin walking with the assistance of a physical therapist and a walker. While most of my total joint replacement patients can be discharged to home within 48 hours, many are stable for discharge within 24 hours of surgery.