|

Some patients experience some mechanical sensations after knee replacement surgery. This is generally a normal consequence of the "hard bearing" components of the knee replacement prosthesis. Let me explain.

Cartilage is a coating of connective tissue that cushions the ends of the bones where the come together at a joint. This material, when healthy, is very slippery and provides some shock absorption to the bones. Healthy cartilage will allow a normal joint to move silently and painlessly. As the cartilage gradually wears out, it may fray, or pieces may break off. Now the joint surfaces are not perfectly smooth. The friction experienced with joint motion increases. As the cartilage layer thins out, its ability to cushion the bone ends also decreases. This all causes increased stress to the bones resulting in pain and stiffness. In response to the stress, the bone density often increases, bone spurs and/or areas of erosion may form, and the joint alignment may change. While these changes usually occur gradually over time, sometimes the progression may be rapid. X-rays will show joint space narrowing (loss of cartilage), sclerosis (increased bone density), osteophytes (bone spurs), cysts (areas of bone erosion). In addition to pain, a patient may experience grinding or crunching sensations from this increased friction and malalignment. These sensations are called crepitus. When we perform total knee replacement surgery, we precisely remove a few millimeters of bone from the end of the femur, tibia, and the undersurface of the patella. This is done in such a way that the prosthetic components will precisely fit the bones, re-align the mechanical axis of the leg, and balance the ligaments that support the joint. Because the prosthesis is metal and plastic, the bone ends no longer have any sensation where they come together. However, the joint surface is no longer soft cartilage, it is hard metal and plastic. Sometimes when these materials move relative to each other a patient may experience this as a clicking or other mechanical sensation. Early after knee replacement surgery, there will be blood and inflammatory fluid within the joint. When the knee is fully extended and the quadriceps are relaxed, the patella may "float" up, away from the femoral component where it normally rests. When the knee is then bent, or the quadriceps are contracted the patella will be pushed firmly down against the femoral component. This will feel like a click or a clunk. The click will not be painful, and will resolve as the fluid is reabsorbed from within the knee. Certain knee replacement models will substitute for the posterior cruciate ligament. This ligament prevents the tibia from moving posteriorly relative to the femoral component. This is accomplished using a polyethylene post on the tibial component. This post will engage against a bar on the femoral component when the knee is flexed and the tibia is pushed posteriorly. This engagement can feel like a click. Again, this is painless. The knee joint normally has a millimeter or two of laxity when stressed sideways. Pushing the tibia inward relative to the femur, and pushing the tibia outward relative to the femur tensions the lateral collateral and medial collateral ligament, respectively. Because there might be slight separation of the femoral and tibial components when applying these stress, a patient can experience a clicking sensation when the tension is removed and the prosthetic components re-engage. Using robotics during knee replacement surgery facilitates very accurate soft tissue balancing throughout the full knee range of motion. This accuracy of ligament balancing allows me to use a posterior cruciate retaining prosthesis (no post to engage) and minimizes side to side laxity. While some mechanical sensations can still occur (particularly with patellofemoral engagement early after surgery as described above), these sensations are minimized. These are the most common reasons a patient may feel some clicking in their knee following knee replacement surgery. When this occurs in the absence of pain, it is likely normal. If there is any question, I recommend you see your surgeon for an evaluation and reassurance.

0 Comments

While some patients have a very easy time rehabilitating their knee replacement, the majority of patients find this surgery challenging to recover from. As surgeons, we do our best to provide clear instructions, multimodal pain control, encouragement and support to our patients. Even my own patients, who I personally counsel in the office, and are then directed to this website, often end up falling behind the ideal rehabilitation schedule because of this mistake.

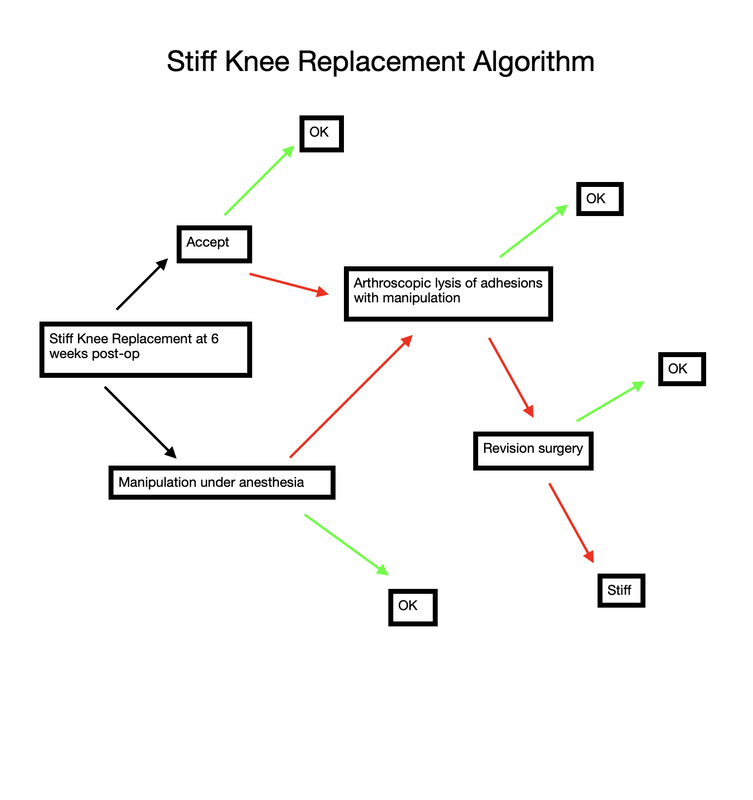

What is this mistake? The mistake is finding an excuse not to stretch your knee. Excuses fall into a couple categories. A common category relates to physical therapy. "My therapist couldn't get me in for 7 days following surgery." "The therapist was sick and canceled several visits." "I am only getting 2 PT sessions each week." "My physical therapist only told me to stretch for 5 seconds each day." Some of these relate to scheduling, and some are clearly misunderstanding/miscommunication. I can't imagine anybody honestly expecting a good result after surgery stretching for a few seconds each day, certainly not a legitimate physical therapist. Other reasons for falling behind relate to the normal inflammatory process we expect after surgery. "My knee felt (hot/tight/swollen, etc)." "I was letting it heal a bit and feel better before stressing it." A third category involves what exactly I mean by rehabilitation. "I have been doing a ton of walking." I have been using my stationary bike." "I have been going up and down stairs." Please, please, please don't get caught in this trap. I know that total knee rehabilitation is unpleasant. I know that it seems strange for me to ask you to stretch a painful, swollen joint. The problem is that any delay in stretching your new knee replacement will make subsequent gains more difficult. Each day that goes by allows the capsular tissues to contract a bit more, allows scar tissue and adhesions to grow and thicken. Take personal responsibility for your own rehabilitation. Begin stretching immediately. Check out this website. It was primarily designed to help you recover after surgery. I have articles and videos explaining how to rehabilitate your knee replacement properly. I explain how often to stretch and for how long. I provide a timeline for recovery. Do not wait for a physical therapist to tell you what to do. You already know what to do. Use them as a resource. Impress them with how much range of motion you regain between physical therapy sessions. Do not expect them to rehabilitate your knee for you. That will not provide an excellent outcome. While walking/biking/etc. are fine things to do, they are really not ideal exercises for regaining knee range of motion. Walking requires very little knee range of motion, and even a stationary bike will not optimize stretching. This is why I direct patients to long duration, passive stretching exercises. These exercises are the most efficient way to recover motion following knee replacement surgery. Expect your knee to swell. It will become discolored. It will feel tight. It will hurt. Do not let these symptoms hold you back from stretching. My rehabilitation recommendations are made expecting these symptoms to occur. Swelling, bruising, and pain are all a normal part of the recovery process. Do not wait for them to resolve before stretching. If you wait, you are likely to compromise your outcome. A stiff total knee replacement can be extremely frustrating for patients and surgeons. The best way to manage a still total knee is prevention. I have written many articles on this website focusing on how to rehabilitate your knee replacement effectively. Unfortunately, some patients will experience stiffness in spite of their best efforts. The management pathway I have outlined below is how I recommend dealing with this problem. For a bit more explanation, check out the video posted below. As you navigate through this website, it should become quite clear how much I emphasize regaining range of motion as soon as possible after knee replacement surgery.

how-to-rehabilitate-your-total-knee-replacement.html another-way-to-stretch-your-knee-replacement.html the-best-total-knee-extension-stretch.html Ability to walk does not indicate adequate knee range of motion. One of the first questions I ask my patients at each follow-up visit after undergoing knee replacement surgery is: " How is your range of motion doing?" For some reason, a very common response is: "I am able to walk (x amount of ) distance." Clearly patients value ability to walk. And while I agree that walking is important, it is crucial to understand that regaining knee range of motion early after knee replacement is absolutely crucial to an excellent long-term outcome. Try a quick experiment. Take a few steps trying to keep one of your knees as straight as possible. See? It can be done. You will have a strange gait, but you can walk with almost no knee range of motion. Now walk normally while watching your knee move. Once again, very little range of motion is required to walk normally. Now sit in a chair and put your feet flat on the ground in front of you. Notice how your knees are bent to around 90 degrees. Now without bending your knees beyond 90 degrees, try to get up from a seated position without pushing off with your arms or thrusting your upper body foward to generate momentum. It is not possible. This is because your center of gravity is behind your feet. To stand up from a seated position, you simply must be able to bend beyond 90 degrees. It is essential to regain functional range of motion by 6 weeks after surgery. Remember, patients can only reliably regain knee range of motion for the first 6 weeks following knee replacement surgery. Beyond this point, scar tissue becomes too stiff and inflexible for simple stretching to be successful. When patients have not achieved an acceptable, functional range of motion by 6 weeks postoperatively, I recommend manipulation under anesthesia. My message is NOT - "Don't walk." Walking is important. It helps to prevent blood clots, it will help reduce swelling, and it is good for the lungs after surgery. Walking is just not sufficient to obtain an excellent result following knee replacement. As much as patients are focused on walking as a sign of recovery, I focus on regaining knee range of motion as the true indication of progress. To summarize: 1- Walking is important to patients and surgeons following knee replacement. 2- Walking does not require very much knee range of motion. 3- A patient's ability to walk after knee replacement does not necessarily indicate adequate knee rehabilitation. 4- The focus, particularly early after knee replacement (first 6 weeks), must be on regaining as much knee range of motion as possible. 5- The closer your knee range of motion is to normal following knee replacement, the more functional your knee will be for all activities (not just walking). 6- There is a limited time period (6 weeks) after a knee replacement for a patient to reliably regain range of motion. This is why I fixate so much on regaining motion as soon as possible after surgery. 7- Walking, comfort, confidence, strength, coordination, and endurance all will improve for months/years after knee replacement surgery. These factors all are improved when a patient has regained excellent range of motion. This means we should be patient with all of these parameters while focusing on early, consistent stretching to help ensure a good result.

Flexing the hip while also flexing the knee focuses most of the stretch on the knee joint. These first two videos demonstrate different ways to accomplish that. In the video below, notice how I am using my torso to generate the force needed to flex the knee. I then take up the slack created in the yoga strap with my arms. Also feel free to use your other leg to help generate flexion force as I demonstrate. The next video demonstrates how to use the strap to improve knee flexion while keeping the hip extended. This is done in the prone position. This will focus more of the stretch on the quadriceps muscle. I recommend stretching in each of these positions for the best result. Excellent knee function also requires full knee extension. The strap can help you achieve this as well. In the following video, I loop the strap over the knee to be stretched. I then place my other foot through a loop in each limb of the strap so that it does not touch the ground, but applies an extension force to the knee. The use of a yoga strap for knee replacement rehabilitation is certainly not mandatory, but simply provides another option to assist you. Always remember to use ice after stretching, hold the stretches for as long as possible, and relax your mind and muscles as much as possible during the stretch.

,It has been customary for decades to use a pneumatic tourniquet during total knee replacement surgery. Inflation of the tourniquet initiated the very first total knee replacement I saw as a medical student, every total knee replacement I did during training, and nearly every total knee I performed while in practice.

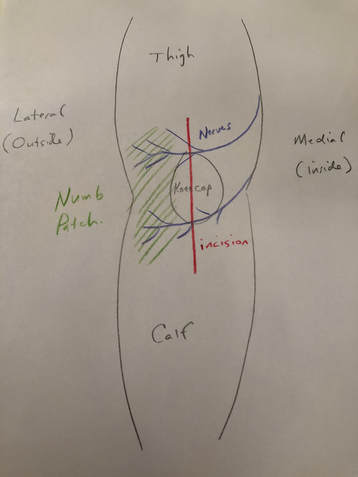

The perceived benefit of tourniquet use was reduced blood loss and better visualization of the tissues during surgery. Total blood loss is defined as any blood loss during surgery, PLUS any postoperative blood loss into dressings or drains, or into the joint or leg. This can be quantified by comparing pre-operative hematocrit (blood count) with the lowest post-operative hematocrit. A recent paper suggests that total blood loss paradoxically INCREASES if a tourniquet is used during surgery. A variety of additional recent papers suggest the same thing. How can this be? Reactive Hyperemia (a period of increased blood flow after tourniquet release) While a tourniquet is inflated, arterial inflow to the limb is stopped. This is nice for the surgeon during the operation as visualization is easier, and no time needs to be spent controlling bleeding. Many surgeons release the tourniquet at the conclusion of the operation, but prior to closing the incision. This allows any bleeding to be controlled. This was what I always did, because I wanted to be sure all active bleeding was stopped prior to wound closure. I hoped to minimize any post-operative bleeding as well as total tourniquet time. Some surgeons do not choose to do this but maintain the tourniquet until a compressive dressing has been applied. The problem is that after the period of ischemia (no blood flow), the tissues demand more blood supply, and the blood flow to the limb increases for a period of time after surgery. This is known as reactive hyperemia. As a result, sometimes after surgery, blood will collect in the knee, accumulate in the dressing, and/or be removed in a drain. This can be uncomfortable for patients and it increases total blood loss. There are other downsides of tourniquet use. Intravenous antibiotics are given just prior to initiation of surgery to help reduce the chance of infection. While this medication is infused prior to tourniquet inflation, once the tourniquet is inflated, blood is no longer circulating and thus, antibiotic medication is not circulating either. Ischemic tissues will become cold making cellular activity and enzymes less effective. Ischemia is stressful to the tissues. This increases inflammation. The tourniquet applies significant pressure to the soft tissues. This can contribute to pain and bruising of the thigh postoperatively. Because the tourniquet stops blood flow, it also increases the chance of blood clot formation. I encountered occasional cases where the tourniquet didn't work well. This can happen if a patient has high blood pressure, their arteries are calcified, or if their thigh is large. In these cases the tourniquet restricts venous outflow but allows arterial inflow since arterial pressure is higher. We refer to this as a "venous tourniquet." When this happened I would drop the tourniquet and carry on as usual. The operation went fine. A bit more time was needed to stop bleeding during surgery, but the results were no different than when using a tourniquet. Based on this, the theoretical negative tourniquet effects, and the recent papers suggesting tourniquet paradoxically increases total blood loss, I decided to stop inflating the tourniquet for total knee replacements. I spend a few more minutes controlling bleeding during the surgical approach. Once this initial bleeding is controlled, there is minimal ongoing blood loss for the remainder of the case. This is analogous to total hip replacement where tourniquet use is impossible due to the location of surgery. Visualization is excellent. The bone ends are irrigated using pulsatile lavage, and dried as usual prior to implanting the knee replacement components. By this stage of the operation, the knee looks basically the same as it does when using a tourniquet. Prior to closure, all bleeding has stopped. No drain is necessary. Tranexamic acid is a medication that helps reduce blood loss, and we use this in most patients. I have been very pleased with the results since I have discontinued routine use of the tourniquet for total knee replacement surgery. I found patients are more comfortable and there is noticeably less swelling and bruising. Knee range of motion has been returning quicker. We are continually working on process improvement to allow patients to return to their normal life as rapidly as possible. This begins with preoperative education, continues with a multimodality pain management plan, a 3-dimensionally planned, robotically assisted joint replacement operation, and early mobilization. My experience is that discontinuing use of the pneumatic tourniquet is yet another step to help patients recover quicker. Nearly every patient will experience some degree of permanent numbness on the lateral (outside) side of the knee after knee replacement surgery. This is anticipated. It is so common, most surgeons do not discuss this with their patients prior to surgery. It is not a complication, but a necessary side-effect of achieving a safe exposure to perform knee replacement surgery.

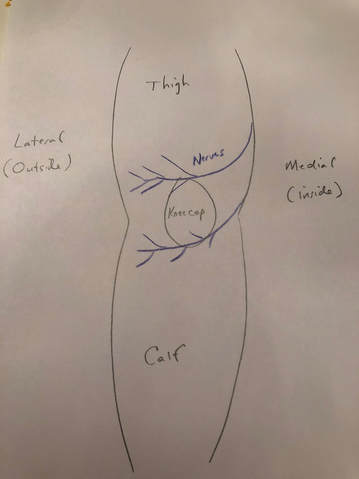

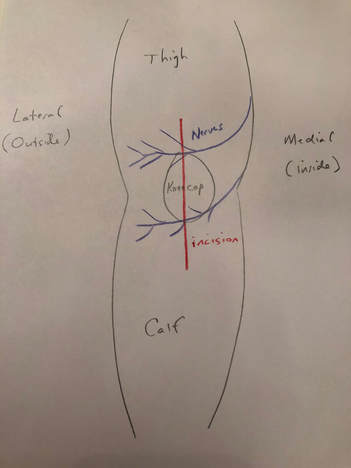

What is going on? There are cutaneous (skin) nerves that cross the front of the knee from the inside (medial) to the outside (lateral). A knee replacement incision is made longitudinally over the front (anterior) of the knee. These small nerves must be cut to allow deeper exposure. Other than a numb patch on the outside of the knee, there is generally no other negative effect. Once rehabilitated, patients rarely even mention this finding. Most are just thrilled their arthritic pain is gone and they are back to their desired activities again. The future is here!

We are thrilled to announce that we are establishing a robotically assisted total joint replacement program here in Hudson, New York. We will be using the Stryker Mako system for partial knee replacements, total knee replacements, and total hip replacements. What is the big deal? Accuracy. Patients and surgeons are very fortunate in that total joint replacement is reproducible, predictable and forgiving. That does not mean it is perfect. While patients routinely report dramatic pain relief once rehabilitated, we as surgeons are thrilled when they report that their new joint feels "normal." This occurs less often than anyone would like. During surgery, we use alignment guides designed to produce certain angles, or remove a particular amount of bone. These guides have been the same for decades. Good surgeons will achieve consistent results, but even the very best surgeons will admit that there is more variability than anyone would like. This can occur for a variety of reasons, but it is impossible to completely avoid. Using a robotic arm during surgery, we can implant joint prostheses within a millimeter and a degree of the intended plan. Every time. No surgeon, anywhere, can do this using manual tools. Before you begin imagining a robotic arm like those seen in vehicle assembly, let me explain how the Styker Mako robotic arm works. Preoperatively, the patient undergoes a CT scan. The surgeon then plans the surgery virtually on the computer, determining the intended alignment and position of the prosthesis. In the operating room, the surgeon makes the surgical approach and then uses a probe to orient the robotic software to the position of the patients bones. During preparation of the bone, the robotic arm prevents anything but the exact plan from being executed. It does this passively. At no point can the robot move itself. The surgeon positions the tools and prostheses and once perfectly aligned, the robot locks the tool into this perfect position. The handpiece, which is operated by the surgeon, will not be activated until it is perfectly aligned and in a safe position. The surgeon then activates the tool, or manually impacts the prosthesis depending on the step in the procedure. The surgeon gets real-time information regarding implant position as it is happening. From the surgeon's perspective, this information is invaluable! We can adjust our plan intraoperatively if needed. We can execute our plan perfectly, every time. During knee replacement, we can balance ligaments degree by degree. During hip replacement, we can optimize acetabular (socket) placement, leg length, and offset. When dealing with complex biological systems, there will always be factors beyond our control. Robotic total joint replacement is an amazing tool, which gives us tighter control over prosthetic implantation and soft tissue balance. This will improve the function and longevity of implants for patients. Much of this website is directed toward proper rehabilitation after joint replacement. While prosthetic alignment and soft tissue balance will be improved using the Mako robot, appropriate rehabilitation will always be crucial to maximizing outcomes. Total knee replacement has become a very common elective surgery, and patients are often amazed at how quickly they can get back to "normal" life after surgery. Within hours of their surgery, my patients are often able to begin walking with the assistance of a physical therapist and a walker. While most of my total joint replacement patients can be discharged to home within 48 hours, many are stable for discharge within 24 hours of surgery.

In spite of the anticipated rapid early recovery following total knee replacement, there is still a significant healing process that must occur. This healing process progresses through an inflammatory cascade and continues for over a year from surgery. It is this inflammatory cascade that requires a dedicated stretching regimen to ensure optimal knee range of motion following surgery. Many patients are concerned that their knee feels warm, and may appear swollen and/or pink in the early post-operative period following knee replacement. In the vast majority of cases, this is normal and an anticipated part of the recovery period. Of course, if there is ever a concern, you should always discuss this with your orthopedic surgeon. Why does this happen? Basically, the body increases blood flow to the knee region to support the healing process. This increased blood flow results in the warmth, swelling and redness often experienced by the patient. As the healing process progresses, the warmth, swelling and redness dissipate. The warmth can take 6 months or longer to resolve. Swelling and redness generally resolve within a few weeks of surgery. A bone scan is a nuclear medicine radiological study that reveals bone metabolic activity. It will light up in areas that are irritated such as fractures, stress reactions, tumors and arthritic joints. If a bone scan is performed within 2 years of a total joint replacement, it will show increased bone metabolic activity adjacent to the relatively new prosthesis (even when the prosthesis is functioning properly). This is further indication that the healing process following joint replacement progresses over a very long period of time. Thankfully, the replaced joint usually feels great, long before the body has fully recovered. So, after total knee replacement you can monitor the healing process by feeling the skin overlying your knee. As your skin gradually cools off, month-by-month, you know the healing process is winding down. Please note: Severe swelling/redness, drainage from the wound, increasing pain, and/or loss of range-of-motion should not be assumed to be normal. If there is any concern, you need to be evaluated by your orthopedic surgeon immediately.  When is it safe to drive after knee replacement surgery? When is it safe to drive after knee replacement surgery? When can I drive? This is a very common question patients ask following surgery. Some studies have suggested that reaction time and/or braking force is reduced for weeks or even months following total knee replacement surgery. This could lead us to recommend that patients do not drive for a prolonged period of time following total knee replacement surgery. Logistically, this can be challenging. A recent study showed that patients with osteoarthritis of the knee (without having undergone knee replacement surgery) had reduced driving ability based on diminished reaction time, movement time, and they ultimately had reduced braking performance. In spite of these findings, is not reasonable to tell patients with osteoarthritis of the knee that they can never drive. A brand new article in the Journal of Arthroplasty shows that 80% of patients have regained their pre-surgery braking performance by 2 weeks following total knee replacement. All patients in this study were back to baseline by 4 weeks. This reinforces my standard recommendation, but still leaves out one key issue. Pain medication. Narcotic pain medication is commonly used for several weeks following total knee replacement. This can impair driving skill and reaction time independent of knee surgery. My recommendation to patients after total knee replacement surgery is that they should not drive while they are using narcotic medications. Furthermore, they should not drive until they feel comfortable doing so. This time period is patient specific, and there is a wide range. Common sense should prevail. I believe patients generally know themselves, and certainly do not want to place anyone at risk by driving prematurely. I recommend patients focus as much as possible on rehabilitating their new total knee replacement for the first few weeks, limiting their driving to the essentials: food shopping, physical therapy, and follow-up with their orthopedic surgeon. Soon, their pain level will be down, and their confidence to drive will return. We can then add driving to the list of lifestyle improvements made possible by total knee replacement. As always...please discuss specific recommendations with your surgeon.

How much motion should you have at any given point after surgery? Of course, you should speak to your surgeon about the specifics of your case. However I'd like to provide some general guidance on this subject.

During knee replacement surgery, the knee will be reconstructed using a metal and plastic prosthesis, and the ligaments balanced. At the conclusion of the operation, the knee will be able to fully extend (straighten) and fully flex (bend back). After surgery, although initially pain will prevent full range of motion, scar tissue has not had a chance to form. Most patients are able to move from full extension (0 degrees) to 90 degrees (foot flat on floor while sitting in normal chair) within 24-48 hours. It is not uncommon for patients to lose a bit of motion around 7-10 days from surgery. This is a result of increased pain and swelling due to the inflammatory cascade. This inflammation peaks around 10 days from surgery. It is ok to go a bit easy on yourself during this time. Use plenty of ice and anti-inflammatory medication if it is allowed by your surgeon. But keep stretching. Do not allow yourself to lose full extension. This is crucial. By the first postoperative visit around 2 weeks from surgery I would like to see a minimum of 0-90 degrees of motion. By 6 weeks from surgery I would like to see 0-120 degrees minimum. Patients may gain an additional 5-10 degrees of deep flexion over the course of the first year following surgery if they've gotten to 120 degrees by 6 weeks. If these parameters are not met, other options are available. I begin asking patients to follow-up with me every other week or more to track their progress, to answer questions, and provide motivation and support. I understand that this process isn't always easy and is never fun. If inadequate range of motion isn't achieved by 6 weeks, I then recommend manipulation under anesthesia to break up scar tissue that has been allowed to form. This buys us some time and generally gets things back on track. total knee Total knee replacement surgery is an effective way to relieve arthritis pain when non-operative measures have failed. A substantial portion of the outcome, however, is based on adequately rehabilitating after surgery. The most important part of the rehabilitation program is regaining normal range of motion. This is easier said than done. At the time of a properly performed knee replacement surgery, the soft tissues are balanced and the range of motion should be full. That is: all the way straight, to all the way bent. This is something we test during surgery. Then the incision is closed and the healing process begins. Initially, there could be some swelling and acute surgical pain from the incision/surgical approach. Soon this acute pain subsides and stiffness begins. The stiffness is experienced by many patients as pain, especially when moving against the endpoint. In a prior posting I discussed the tissue planes that need to glide to allow proper motion. Each day that passes after knee replacement surgery, more healing occurs. This process can create connections, or adhesions, between these tissues. After about 6 weeks, enough scar tissue has formed, that most patients are unable to obtain more range of motion by stretching. In other words, at around 6 weeks from surgery no more progress with regard to range of motion is possible. The trouble is, in order to regain excellent function, adequate knee range of motion is necessary. Most patients are anxious to walk, ride a stationary bike, and are often quite focused on regaining strength. While these are fine things to do, and I certainly understand this desire, redirecting the focus to stretching appropriately remains my priority during the first 6 weeks postoperatively. Once range of motion is reestablished, all of these activities will be possible. Because we have a limited time to regain this range of motion this needs to be the priority early on. Thankfully these stretches are simple. Gently and progressively force the knee straight. And then gently and progressively force the knee bent. Simple! Except when it's not. Sometimes, and fortunately it is rare, a patient really struggles to regain range of motion after their total knee replacement. This can be a very frustrating situation for the patient and surgeon alike. I recommend stretching early, often, gently, but progressively. It is better to regain motion early than to attempt to catch up when stiffness is setting in. The simplest stretches are shown below:  knee extension stretch knee extension stretch This is one of the easiest stretches for extension. Place your ankle on a pillow. Relax your muscles to allow your knee to sag down. Then attempt to push the back of your knee down. This is a side view of my knee. It is important to note that my kneecap and toes are pointing straight up. This stretch can be held for minutes, gradually relax your muscles more and more, allow gravity to do the work. The longer the stretch the more the viscoelastic tissues will elongate.  avoid external rotation when doing knee extension stretch avoid external rotation when doing knee extension stretch This is the wrong way to stretch. This is a view of my knee from above. There is a natural tendency to externally rotate as your hips relax. Our goals are not being accomplished if this is allowed to happen. If you find this happening, simply place additional pillows or folded blankets along the outside of your foot and thigh to hold your toes and kneecap pointing up.  knee flexion stretch knee flexion stretch Now we are working on regaining flexion. In this example we are working on gaining flexion in my right knee (in the back ground of this photo). Here I have placed my left leg in front of my right ankle. I am using my left leg to help bend my stiff right knee more. This works best when done progressively over a period of minutes as opposed to seconds. Use your hamstrings in both legs to try to flex both knees further.  deeper knee flexion test using stepstool deeper knee flexion test using stepstool For deeper flexion than the previous stretch, this position utilizes a step-stool to provide deeper knee flexion. As shown, leaning forward and applying pressure with your hands can increase the stretch.  Deepest knee flexion stretch done in supine position Deepest knee flexion stretch done in supine position This is a stretch that can achieve extreme flexion. This time I am lying on my back. My knee is pointing up toward the ceiling. Flexing the hip relaxes the quadriceps. The hands are used to to pull the leg toward your body. The effect is increased hip and knee flexion. Please note: if you have a total hip replacement, be very careful with this position as it can produce significant hip flexion. These stretching positions should take care of 90% of total knee replacement patients. These stretches should be done everyday, ideally multiple times per day, with no days off. The longer the stretches can be held, the better. Remember to relax as much as possible while stretching and remember that a little pain is normal an expected. If no pain is encountered, I would recommend pushing a little bit harder. As always, if you have any specific questions about your particular case, discuss with your surgeon.

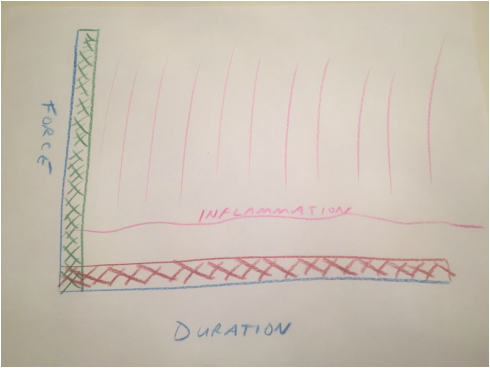

Occasionally we encounter a patient that has a very difficult time regaining motion. I have a few additional recommendations in these cases and will address that situation in an upcoming posting. Biologic tissues are viscoelastic. That means their stretchiness changes depending on how hard they are stretched. We can take advantage of this characteristic when we are rehabilitating a stiff joint. This becomes very important with certain medical problems. Specifically: total knee replacement and frozen shoulder. This concept is generally helpful in orthopedic rehabilitation and I take advantage of it whenever applicable. Think of silly putty. When slowly stretched it can be drawn out into a long strand, but when pulled aggressively it will snap and break in two. This is an extreme example of viscoelasticity. Your tissues are similar. While extreme force stretching can cause tissue to tear, this is generally far beyond any amount of stretching a patient can do, even with a physical therapist. A manipulation under anesthesia is a maneuver performed by a surgeon to rapidly regain motion in a particular joint that has become stiff. Tissues tear, and inflammation results. This is the most extreme example of a high force, low duration stretch. It is best to avoid this type of intervention if possible. It is preferable for a patient to spend the time necessary to recover joint range of motion using a long duration, low force stretch. It will result in less inflammation and less pain. Shoulders and knees commonly become stiff. Total knee rehabilitation requires stretching to regain range of motion after surgery. Stretching is required to speed up the recovery of a frozen shoulder. When attempting to regain range of motion patients are often told to stretch for 10-15 seconds and then relax. Over and over. Sometimes this is effective. Sometimes it is not. There is significant genetic variation with regard to tissue strength and inflammatory response, and significant psychological variation with regard to pain tolerance, and ability to relax while stretching. When a patient has trouble regaining range of motion I try to focus them on long duration, low force stretching. This tends to create less inflammation and is more likely to allow a patient to relax the muscles while stretching. Relaxing is very important because any muscle resistance will prevent gains in range of motion.  Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. This sketch depicts how I think about stretching. A high force, brief stretch is more likely to cause inflammation. A gentle prolonged stretch is less likely to create an inflammatory response. The "amount of stretch" or the total area under the curve depicted by the hash marks could be identical, but my experience suggests the long duration, low force stretching will give a superior result. How do I know this? When I was a resident, I developed a frozen shoulder and used long duration, low force stretching to cure myself. I have subsequently recommended this technique to countless patients who presented with frozen shoulders that had failed to improve after many weeks of standard physical therapy. Although occasionally surgical intervention was necessary, the vast majority progressed using this technique and never needed surgery. This technique has become my standard recommendation following total knee replacement and to rehabilitate a frozen shoulder, and has minimized the need for manipulation.

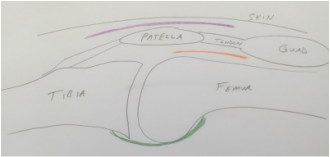

So you finally decided to have your arthritic knee replaced. You got through the surgery just fine. As expected, you had some surgical pain, but almost immediately you realized that your arthritic pain was gone. Awesome! Things seemed to be going very nicely, and now you are home... Your knee may begin feeling tight and warm. This is normal and expected. Healing occurs in part through an inflammatory process. Inflammation shows up as swelling, warmth, and pain. You have been told to stretch, but may be questioning this recommendation now. You may be concerned that because it hurts you could be damaging yourself or your new knee. This is a very common concern. Please resist the urge to stop stretching. The knee is a complex joint. There several moving parts and potential spaces (otherwise known as tissue planes). During total knee replacement these parts are moved around , the tissue planes are opened. I think it makes sense to patients when they have some pain after surgery. But as the wound is healing on the outside, why does it feel like things are getting worse on the inside? As the healing process proceeds, the tissue planes that have been opened begin sticking together. Gradually adhesions, or scar tissue, may form between these planes preventing them from gliding properly. Initially this scar tissue is weak, but it will get stronger every day. For this reason, there is some urgency to regain range of motion as soon as possible. This is because after about 6 weeks or so from surgery this scar tissue becomes strong enough that a patient is unlikely to be able to stretch it out any more. The range of motion you have achieved at this point will be how far your knee will move permanently...without additional intervention. To better understand knee range of motion lets begin with a couple of definitions. Flexion of the knee means bending. When you sit in a chair and your feet are flat on the floor, your knee is bent, or flexed. Extension of the knee means straightened. When you stand up and your knee is straight it is extended. Now lets discuss these tissue planes a bit.  Tissue layers in the knee that must be stretched following total knee replacement. Tissue layers in the knee that must be stretched following total knee replacement. The skin must be able to slide over the kneecap (patella). The body achieves this by only loosely attaching the skin to the patella. This loose connective tissue allows motion to occur. Under abnormal conditions, fluid can collect here and create swelling. A potential space such as this is referred to as a bursa. The loose connective tissue found here is called bursal tissue. The specific space, or tissue plane, between the skin and the kneecap is called the pre-patellar bursa. It is shown in purple in my sketch. The kneecap (patella) is embedded within the tendon that attaches your thigh muscles (quadriceps) to your shin bone (tibia). A tendon is the tissue that attaches muscle to bone. The quadriceps tendon must be able to slide relative to the thigh bone (femur). The area above the patella shown in my sketch as orange is called the supra-patellar pouch. If either of these tissue planes sticks together, the knee will not be able to bend completely. In the back of the knee there is a sheet of tissue called the posterior capsule. This is green in my sketch. This tissue is irritated during surgery and will gradually tighten as it heals. If this is allowed to happen, the knee will not fully extend. So, how do you prevent a stiff total knee? It is not by walking around a lot. It is not by cycling the knee back and forth a lot. It is by gently and progressively stretching. Even though it hurts. The longer you are from surgery, the longer these stretching sessions must be because the scar tissue becomes stronger each day. Gentle progressive stretching works by taking advantage of the viscoelastic nature of biologic tissues. My basic recommendations:

|

Dr. GorczynskiOrthopedic Surgeon focused on the entire patient, not just a single joint. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed