|

In a previous post, I described what I feel to be the most important shoulder stretch. It is very important functionally to be able to reach out in front of you, and to reach overhead. While my focus in the prior post was frozen shoulder (otherwise known as adhesive capsulitis), the stretch I described is very useful for regaining function after rotator cuff surgery, shoulder labral repair surgery, and trauma. The anterior and inferior (front and bottom) shoulder capsule/ligaments are stretched using this technique. (Please note: If you are dealing with a frozen shoulder, this stretch may be too irritating to begin with. I recommend you begin with anterior, inferior capsule stretching using the best stretch for a frozen shoulder. You can come back here once you have regained the ability to raise your arm over your head again.) Sometimes, in spite of having done an outstanding job rehabilitating their shoulder following surgery, a patient may have some residual pain. Another common subset of patients presents with shoulder impingement syndrome or bursitis. These patients report pain which is usually lateral arm pain, aching in character, and may be worse at night. If forward elevation (reaching overhead), and abduction (reaching out to the side) are near normal, and rotator cuff strength is good, it is important to focus on the posterior capsule (ligaments in the back of the shoulder). A tight posterior capsule can cause abnormal shoulder mechanics. This can cause the shoulder ball (humeral head) to translate superiorly (upward) when raising the arm instead of rotating in the socket (glenoid). This pinches the rotator cuff and causes pain. The rotator cuff normally pushes down on the humeral head during rotation, but when it is irritated it will get lazy. Unfortunately, this compounds the problem, and allows the humeral head to further translate upward during activities. A cycle is then created whereby the problem gets progressively worse. We need to break this cycle. When I find the posterior capsule to be tight, I recommend using the sleeper stretch. This is a simple stretch that a patient can do on their own. As always, I recommend stretching every day, with no days off. I also recommend gentle progressive static stretching. That is, slowly applied pressure that is then held at the endpoint for relatively long duration. This means minutes rather than seconds. We are taking advantage of the viscoelastic nature of our soft tissues. The posterior capsule tends to be relatively thin tissue, and thus, this stretch does not require high force.  Posterior Capsule Stretch (Sleeper Stretch) Posterior Capsule Stretch (Sleeper Stretch) In these photos I am lying on my side. For this demonstration we will assume my right shoulder is the bad one. So, I am lying on the bad side. My elbow is out in front of me. The upper arm should be even with the shoulder. Both palms are facing toward my feet. Now gently and progressively apply force with the left hand. The goal should be to create rotation of the right palm toward the floor. This should create tension and stretching pain in the back of the shoulder. Ordinarily I would recommend resting your head on a pillow for comfort. I am not doing this to avoid obscuring the positioning.  Posterior Capsule Stretch (sleeper stretch), viewed from above. Neutral position. Posterior Capsule Stretch (sleeper stretch), viewed from above. Neutral position. Here is the view from above. Again note my upper arm is at shoulder level and my palms are facing toward my feet. Pressure is applied rotating my right shoulder internally, and pushing palms toward the floor.  Posterior capsule stretch with torso leaning slightly back. This is a less aggressive position. Posterior capsule stretch with torso leaning slightly back. This is a less aggressive position. Here is a less aggressive position. It may be good to begin this way. You can place a pillow behind your back to lean against. For all of these positions, resting your head on a pillow will allow more relaxation and thus a more pleasant stretch that you can hold for a longer time period.  Posterior capsule stretch (sleeper stretch) with torso leaning forward. This is a more aggressive position. Posterior capsule stretch (sleeper stretch) with torso leaning forward. This is a more aggressive position. This is the most aggressive sleeper stretch position. This will concentrate more force on the posterior capsule. It may not always be necessary to regain balance. I recommend testing each of this positions on the other (good) side so you have a benchmark to assess what is normal for you. Some key points:

0 Comments

How much motion should you have at any given point after surgery? Of course, you should speak to your surgeon about the specifics of your case. However I'd like to provide some general guidance on this subject.

During knee replacement surgery, the knee will be reconstructed using a metal and plastic prosthesis, and the ligaments balanced. At the conclusion of the operation, the knee will be able to fully extend (straighten) and fully flex (bend back). After surgery, although initially pain will prevent full range of motion, scar tissue has not had a chance to form. Most patients are able to move from full extension (0 degrees) to 90 degrees (foot flat on floor while sitting in normal chair) within 24-48 hours. It is not uncommon for patients to lose a bit of motion around 7-10 days from surgery. This is a result of increased pain and swelling due to the inflammatory cascade. This inflammation peaks around 10 days from surgery. It is ok to go a bit easy on yourself during this time. Use plenty of ice and anti-inflammatory medication if it is allowed by your surgeon. But keep stretching. Do not allow yourself to lose full extension. This is crucial. By the first postoperative visit around 2 weeks from surgery I would like to see a minimum of 0-90 degrees of motion. By 6 weeks from surgery I would like to see 0-120 degrees minimum. Patients may gain an additional 5-10 degrees of deep flexion over the course of the first year following surgery if they've gotten to 120 degrees by 6 weeks. If these parameters are not met, other options are available. I begin asking patients to follow-up with me every other week or more to track their progress, to answer questions, and provide motivation and support. I understand that this process isn't always easy and is never fun. If inadequate range of motion isn't achieved by 6 weeks, I then recommend manipulation under anesthesia to break up scar tissue that has been allowed to form. This buys us some time and generally gets things back on track. total kneeIn an earlier post, I described my experience with a frozen shoulder. Here are some pictures showing exactly how I rehabilitated myself and how I recommend my patients stretch on a daily basis.  The best stretch for frozen shoulder - starting position - side view The best stretch for frozen shoulder - starting position - side view The initial position will look something like this. I am using a jar of sauce to provide some downward pressure. My good arm is placed in a similar position and allowed to rest with the shoulder, elbow, and wrist touching the floor. When your bad shoulder is hurting from the stretch, look over at your good shoulder and remind yourself what normal range of motion looks like.  The best stretch for frozen shoulder - side view The best stretch for frozen shoulder - side view This is the goal. Now I am able to touch my shoulder, elbow, and wrist to the floor at the same time. You will not get to this point quickly. It will likely take hours of stretching like this over weeks to go from the first picture to this one.  the best stretch for frozen shoulder - intermediate position the best stretch for frozen shoulder - intermediate position Here is how it looks from above.  the best stretch for frozen shoulder - final position goal the best stretch for frozen shoulder - final position goal Gradually bringing your hand and elbow closer to your head will add additional stretch. Some key points:

Uncommonly, a patient is unable to regain adequate range of motion in a reasonable period of time following total knee replacement surgery. When I observe a patient gradually falling behind with rehabilitation, I begin following them in my office more closely to provide guidance, and motivation. This can be a very frustrating situation for both the patient and surgeon. I have previously written about the tissue planes in the knee that need to be encouraged to glide, and on some stretching techniques to accomplish this. My recommendations are based in part on the viscoelastic nature of these tissues. I believe the quadriceps muscle can sometimes thwart a patients efforts to regain flexion. In the years prior to making the decision to proceed with knee replacement, a patient likely experienced episodes of giving-way or jolts of pain. The quadriceps would need to contract aggressively to prevent the knee from buckling. Additionally, many patients develop an abnormal, stiff-legged gait pattern which likely minimizes joint motion and pain. This quadriceps activity is likely subconscious, but by being repeated over a long period of time create neural pathways in the brain that are hard to break. Postoperatively, the habitual quadriceps contraction in response to pain may make rehabilitation more challenging for these patients. I have developed this idea after hearing many patients explain how hard their physical therapist is pushing on their knee, and it simply will not bend. Ive been told the physical therapist is actually off the ground being supported by the patients knee. It sounds horrible. The only way for this to be possible within the first 6 weeks or so from surgery is for the patients quadriceps to be pushing back. Guaranteed. How can I be so certain? Because of my experience with manipulation under anesthesia. At around 6 weeks from surgery if a patient and I agree that their range of motion is not acceptable I perform this procedure. A patient is briefly placed under anesthesia. I gently flex the knee while flexing the hip. Pressure is then progressively applied through the tibia and soft tissue releasing is felt and sometimes heard while this occurs. The goal is to re-establish the pre-patellar tissue plane (between the skin and the kneecap) and the suprapatellar pouch (between the quadriceps tendon and the femur). Once this has been accomplished the knee will generally flex to 120-130 degrees under the force of gravity alone. This verifies that no more joint adhesions are obstructing motion. So again, how do I know the quadriceps is fighting back? Because it only requires me to apply gentle pressure. Maybe 5-10 pounds of force. Worst case 20 pounds or so. Based on this I recommend focusing on relaxing the quadriceps while stretching. Additionally, consider pre-fatiguing them. This is a technique where you would attempt to extend your knee while blocking it from moving (isometric quadriceps contraction) Then relax the quad and enter directly into the stretch. This can create significant gains. My experience has been most positive with prolonged, low force stretching as opposed to shorter, more aggressive stretches. Relatively early manipulation of a stiff knee when necessary helps the vast majority of patients get back on track. By breaking up immature scar tissue it extends the rehabilitation window a bit. Patients still need to work hard on their stretching exercises on a daily basis, but by using this technique we can "catch them up," and help to ensure adequate function and pain relief.  It is very common for a patient to bring a friend or family member along to their office visit with me. I think this is generally a good thing, as we cover a lot of information in a brief period of time. Studies have shown that patients recall only a small fraction of what was discussed with their doctor. Perhaps a second set of ears can improve this a bit. Some of the more complicated discussions I have with patients concern the decision to proceed with surgery. It is important that patients have reasonable outcome expectations and understand the potential risks involved and the need to commit to thorough and careful rehabilitation. As most of my surgery is elective, at some point the patient must chose to proceed surgically. For elective operations, there is never a "need" or requirement for surgery. It is a lifestyle choice. Each patient has their own risk/benefit analysis. I view my role is to educate regarding the procedure and possible risks, to present all non-operative options, and to make some predictions about potential outcomes based on the patients medical history, and particular problem. When dealing with a chronic progressive problem like osteoarthritis of the knee, patients have usually tried a variety of non-operative treatment options prior to considering surgery. Even when non-operative treatment has failed to adequately control symptoms, patients don't always know if they should proceed surgically. While working through this discussion, I commonly find the 3rd party often suggesting the patient proceed surgically. I do not talk people into elective procedures. And I will often address the 3rd party's comment with a statement of my own: "it's very easy to sign someone else up for surgery." The odds are dramatically in the patients favor when considering most orthopedic procedures. We can reliably achieve meaningful improvements in quality of life. The vast majority of patients, once rehabilitated, tell me they waited too long to proceed surgically. Nevertheless, the point that a patient decides to have surgery is a major turning point in their life. If a patient does not appear convinced that surgery is appropriate, I suggest they not make the decision in the office with me in front of them. I recommend that they go home and think things over, to determine if their quality of life is acceptable as-is. A patient should never feel pressured into undergoing a elective operation. We can always do surgery, but we can never take it away. I think patients intuitively understand this, and often the third party does not. Patients can easily decide to proceed with elective orthopedic surgery when the time is right. The threshold in a particular patient is unique, and is based on countless factors including pain, desired activity level, past experiences, support system, finances, work requirements, etc. The psychology of recovery after orthopedic surgery is extremely important, and I feel under-appreciated. A future post will address the psychology of healing. For now, I will suggest that an excellent surgical outcome begins with positive feelings about the decision to proceed with surgery. When a patient feels it is the right time in their life, that they have exhausted alternatives, that they have a surgeon they can trust, and that they have an optimal support team, the stage has been set for a positive result. Total knee replacement surgery is an effective way to relieve arthritis pain when non-operative measures have failed. A substantial portion of the outcome, however, is based on adequately rehabilitating after surgery. The most important part of the rehabilitation program is regaining normal range of motion. This is easier said than done. At the time of a properly performed knee replacement surgery, the soft tissues are balanced and the range of motion should be full. That is: all the way straight, to all the way bent. This is something we test during surgery. Then the incision is closed and the healing process begins. Initially, there could be some swelling and acute surgical pain from the incision/surgical approach. Soon this acute pain subsides and stiffness begins. The stiffness is experienced by many patients as pain, especially when moving against the endpoint. In a prior posting I discussed the tissue planes that need to glide to allow proper motion. Each day that passes after knee replacement surgery, more healing occurs. This process can create connections, or adhesions, between these tissues. After about 6 weeks, enough scar tissue has formed, that most patients are unable to obtain more range of motion by stretching. In other words, at around 6 weeks from surgery no more progress with regard to range of motion is possible. The trouble is, in order to regain excellent function, adequate knee range of motion is necessary. Most patients are anxious to walk, ride a stationary bike, and are often quite focused on regaining strength. While these are fine things to do, and I certainly understand this desire, redirecting the focus to stretching appropriately remains my priority during the first 6 weeks postoperatively. Once range of motion is reestablished, all of these activities will be possible. Because we have a limited time to regain this range of motion this needs to be the priority early on. Thankfully these stretches are simple. Gently and progressively force the knee straight. And then gently and progressively force the knee bent. Simple! Except when it's not. Sometimes, and fortunately it is rare, a patient really struggles to regain range of motion after their total knee replacement. This can be a very frustrating situation for the patient and surgeon alike. I recommend stretching early, often, gently, but progressively. It is better to regain motion early than to attempt to catch up when stiffness is setting in. The simplest stretches are shown below:  knee extension stretch knee extension stretch This is one of the easiest stretches for extension. Place your ankle on a pillow. Relax your muscles to allow your knee to sag down. Then attempt to push the back of your knee down. This is a side view of my knee. It is important to note that my kneecap and toes are pointing straight up. This stretch can be held for minutes, gradually relax your muscles more and more, allow gravity to do the work. The longer the stretch the more the viscoelastic tissues will elongate.  avoid external rotation when doing knee extension stretch avoid external rotation when doing knee extension stretch This is the wrong way to stretch. This is a view of my knee from above. There is a natural tendency to externally rotate as your hips relax. Our goals are not being accomplished if this is allowed to happen. If you find this happening, simply place additional pillows or folded blankets along the outside of your foot and thigh to hold your toes and kneecap pointing up.  knee flexion stretch knee flexion stretch Now we are working on regaining flexion. In this example we are working on gaining flexion in my right knee (in the back ground of this photo). Here I have placed my left leg in front of my right ankle. I am using my left leg to help bend my stiff right knee more. This works best when done progressively over a period of minutes as opposed to seconds. Use your hamstrings in both legs to try to flex both knees further.  deeper knee flexion test using stepstool deeper knee flexion test using stepstool For deeper flexion than the previous stretch, this position utilizes a step-stool to provide deeper knee flexion. As shown, leaning forward and applying pressure with your hands can increase the stretch.  Deepest knee flexion stretch done in supine position Deepest knee flexion stretch done in supine position This is a stretch that can achieve extreme flexion. This time I am lying on my back. My knee is pointing up toward the ceiling. Flexing the hip relaxes the quadriceps. The hands are used to to pull the leg toward your body. The effect is increased hip and knee flexion. Please note: if you have a total hip replacement, be very careful with this position as it can produce significant hip flexion. These stretching positions should take care of 90% of total knee replacement patients. These stretches should be done everyday, ideally multiple times per day, with no days off. The longer the stretches can be held, the better. Remember to relax as much as possible while stretching and remember that a little pain is normal an expected. If no pain is encountered, I would recommend pushing a little bit harder. As always, if you have any specific questions about your particular case, discuss with your surgeon.

Occasionally we encounter a patient that has a very difficult time regaining motion. I have a few additional recommendations in these cases and will address that situation in an upcoming posting. I began playing ice hockey when I was 7 years old. When I was an orthopedic resident in New York City we formed a Hospital for Joint Diseases orthopedic hockey team. We had the unique opportunity to play outside in central park and also at Chelsea Piers with a view of the Hudson river and the New York skyline.

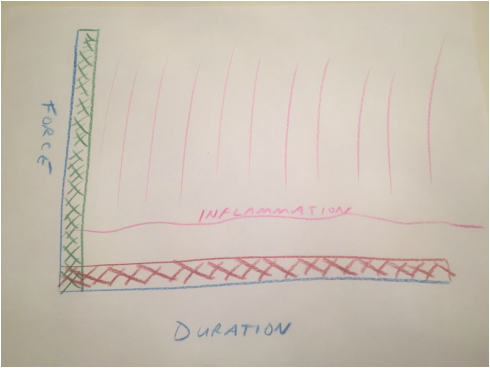

In spite of the violent reputation ice hockey has, I never personally sustained any significant injury. Until one evening around midnight (we had terrible ice times) when I was involved in a collision deep in my defensive zone. The back of my left shoulder made contact with the boards and I felt a zing of pain into the side of my arm. I immediately had difficulty raising my arm. Thankfully, it was toward the end of the game. I liberally applied ice when I got home, but when I woke up in the morning, I still couldn't actively raise my arm. I was fairly certain my injury was a rotator cuff contusion, and not a rotator cuff tear due to the mechanism of injury, and therefore would be self-limited. This proved to be correct, and by that afternoon, my active range of motion had returned, albeit with some pain. Confident my pain would improve as the contusion healed, I went about my normal daily activities for the next several weeks. I grew somewhat concerned however when the pain wasn't decreasing, but rather it was increasing. As a physician, working with world-renowned orthopedic surgeons who would be happy to assist me, I instead chose to ignore it. My life was too busy to deal with my shoulder. I could work, and for the most part I could compartmentalize the pain. Working at shoulder level or below was essentially normal and pain-free. But, if I forgot and suddenly reached for something, a knife-like jab brought my shoulder's issues front and center. After several months went by, I began to feel that my first choice of treatment (doing nothing) had failed. I finally examined my shoulder objectively and noted that although my strength was normal, I had lost some range of motion. More interestingly, I had lost not only active range of motion, but passive range of motion as well. At this instant I understood why my pain wasn't getting better. I had developed a frozen shoulder. Now everything made sense. At this point, I began my rehabilitation program. Everyday after work I applied ice to my shoulder for about 20 minutes. I purchased an ice machine to assist with this. I tried traditional stretching techniques, but was disappointed with the results. I was able to achieve intense pain, but absolutely no increase in range of motion. I actually felt I was getting worse. Frustration is an understatement. A possible treatment for a frozen shoulder that has been resistant to all nonoperative measures is a manipulation under anesthesia. The surgeon essentially forces the joint through a range of motion, tearing the tight tissues. This is something I clearly hoped to avoid. I recognized that biologic tissues are viscoelastic. I felt that based on this characteristic a stretch done gently, but for longer duration could be more effective. And so I began stretching differently. I measured the duration of stretch in minutes as opposed to seconds. I got to the painful endpoint and held it under tension for as long as I could tolerate it. Knowing that the longer I stretched the better it would be I increased the duration of my stretching to 30 minutes or more. Stretching hurts. I reminded myself that in spite of the pain I was experiencing, I was not creating damage. To maintain a stretch of this duration requires you to relax. The best position for me was to lay on the floor on my back and attempt to simultaneously touch my shoulder, elbow and wrist to the floor at the same time. I added some weight to my hand to increase the stretch and watched TV. I did this routine every day. At first I wasn't sure it was helping. But then I instinctively reached for something without thinking. Something that had previously caused a jolt of pain. And I felt no pain at all. This motivated me to add weight and time to the stretching program. Within a few more weeks my shoulder pain had resolved and I had regained normal range of motion. This method has made surgery for frozen shoulder very rare in my practice. When I first describe this technique to my patients, they seem incredulous. Most have already been through a course of physical therapy and are very frustrated. They presented to me to have an operation. But with very few exceptions (sometimes patients with diabetes have very resistant frozen shoulders), the vast majority of patients can avoid the operating room using this method. I will upload some pictures of how I recommend stretching in an upcoming post. Biologic tissues are viscoelastic. That means their stretchiness changes depending on how hard they are stretched. We can take advantage of this characteristic when we are rehabilitating a stiff joint. This becomes very important with certain medical problems. Specifically: total knee replacement and frozen shoulder. This concept is generally helpful in orthopedic rehabilitation and I take advantage of it whenever applicable. Think of silly putty. When slowly stretched it can be drawn out into a long strand, but when pulled aggressively it will snap and break in two. This is an extreme example of viscoelasticity. Your tissues are similar. While extreme force stretching can cause tissue to tear, this is generally far beyond any amount of stretching a patient can do, even with a physical therapist. A manipulation under anesthesia is a maneuver performed by a surgeon to rapidly regain motion in a particular joint that has become stiff. Tissues tear, and inflammation results. This is the most extreme example of a high force, low duration stretch. It is best to avoid this type of intervention if possible. It is preferable for a patient to spend the time necessary to recover joint range of motion using a long duration, low force stretch. It will result in less inflammation and less pain. Shoulders and knees commonly become stiff. Total knee rehabilitation requires stretching to regain range of motion after surgery. Stretching is required to speed up the recovery of a frozen shoulder. When attempting to regain range of motion patients are often told to stretch for 10-15 seconds and then relax. Over and over. Sometimes this is effective. Sometimes it is not. There is significant genetic variation with regard to tissue strength and inflammatory response, and significant psychological variation with regard to pain tolerance, and ability to relax while stretching. When a patient has trouble regaining range of motion I try to focus them on long duration, low force stretching. This tends to create less inflammation and is more likely to allow a patient to relax the muscles while stretching. Relaxing is very important because any muscle resistance will prevent gains in range of motion.  Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. Force vs. duration stretching. A longer stretch done with less force will create less inflammation. This sketch depicts how I think about stretching. A high force, brief stretch is more likely to cause inflammation. A gentle prolonged stretch is less likely to create an inflammatory response. The "amount of stretch" or the total area under the curve depicted by the hash marks could be identical, but my experience suggests the long duration, low force stretching will give a superior result. How do I know this? When I was a resident, I developed a frozen shoulder and used long duration, low force stretching to cure myself. I have subsequently recommended this technique to countless patients who presented with frozen shoulders that had failed to improve after many weeks of standard physical therapy. Although occasionally surgical intervention was necessary, the vast majority progressed using this technique and never needed surgery. This technique has become my standard recommendation following total knee replacement and to rehabilitate a frozen shoulder, and has minimized the need for manipulation.

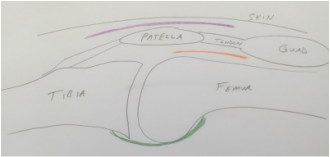

So you finally decided to have your arthritic knee replaced. You got through the surgery just fine. As expected, you had some surgical pain, but almost immediately you realized that your arthritic pain was gone. Awesome! Things seemed to be going very nicely, and now you are home... Your knee may begin feeling tight and warm. This is normal and expected. Healing occurs in part through an inflammatory process. Inflammation shows up as swelling, warmth, and pain. You have been told to stretch, but may be questioning this recommendation now. You may be concerned that because it hurts you could be damaging yourself or your new knee. This is a very common concern. Please resist the urge to stop stretching. The knee is a complex joint. There several moving parts and potential spaces (otherwise known as tissue planes). During total knee replacement these parts are moved around , the tissue planes are opened. I think it makes sense to patients when they have some pain after surgery. But as the wound is healing on the outside, why does it feel like things are getting worse on the inside? As the healing process proceeds, the tissue planes that have been opened begin sticking together. Gradually adhesions, or scar tissue, may form between these planes preventing them from gliding properly. Initially this scar tissue is weak, but it will get stronger every day. For this reason, there is some urgency to regain range of motion as soon as possible. This is because after about 6 weeks or so from surgery this scar tissue becomes strong enough that a patient is unlikely to be able to stretch it out any more. The range of motion you have achieved at this point will be how far your knee will move permanently...without additional intervention. To better understand knee range of motion lets begin with a couple of definitions. Flexion of the knee means bending. When you sit in a chair and your feet are flat on the floor, your knee is bent, or flexed. Extension of the knee means straightened. When you stand up and your knee is straight it is extended. Now lets discuss these tissue planes a bit.  Tissue layers in the knee that must be stretched following total knee replacement. Tissue layers in the knee that must be stretched following total knee replacement. The skin must be able to slide over the kneecap (patella). The body achieves this by only loosely attaching the skin to the patella. This loose connective tissue allows motion to occur. Under abnormal conditions, fluid can collect here and create swelling. A potential space such as this is referred to as a bursa. The loose connective tissue found here is called bursal tissue. The specific space, or tissue plane, between the skin and the kneecap is called the pre-patellar bursa. It is shown in purple in my sketch. The kneecap (patella) is embedded within the tendon that attaches your thigh muscles (quadriceps) to your shin bone (tibia). A tendon is the tissue that attaches muscle to bone. The quadriceps tendon must be able to slide relative to the thigh bone (femur). The area above the patella shown in my sketch as orange is called the supra-patellar pouch. If either of these tissue planes sticks together, the knee will not be able to bend completely. In the back of the knee there is a sheet of tissue called the posterior capsule. This is green in my sketch. This tissue is irritated during surgery and will gradually tighten as it heals. If this is allowed to happen, the knee will not fully extend. So, how do you prevent a stiff total knee? It is not by walking around a lot. It is not by cycling the knee back and forth a lot. It is by gently and progressively stretching. Even though it hurts. The longer you are from surgery, the longer these stretching sessions must be because the scar tissue becomes stronger each day. Gentle progressive stretching works by taking advantage of the viscoelastic nature of biologic tissues. My basic recommendations:

My blog is intended to address common issues I face on a daily basis in practice. Because I focus on total joint replacement of the shoulder, hip, and knee as well as arthroscopic surgery, many of my postings relate to these procedures and the rehabilitation process necessary for the best recovery possible.

I am sure there will be a variety of questions/concerns that I will not spontaneously address. Since my goal is to provide educational resources for patients worldwide, please feel free to suggest a topic you would like to see me address on this website. Please understand that I can not make personal, specific recommendations to you, as we do not have a doctor/patient relationship. I will, however do my very best to address your question in general terms, and as always, I am available for personal consultation if you'd like. Feel free to email me: [email protected] or simply make a suggestion in the comment section below. The difference between active and passive range of motion is easy for surgeons and physical therapists to understand, but is often unclear to patients.

Distinguishing between these two motions is crucial to properly rehabilitate certain surgeries, especially for a rotator cuff repair. Although I do my best to demonstrate each motion, and patients usually voice understanding, it is common for them to then demonstrate that they do not indeed understand. Active range of motion is what we normally do all day every day. Our body normally functions using a coordinated series of active motions. This motion is controlled by muscles. Muscles cross joints, which are where bones meet and move relative to each other. When a muscle contracts, a joint moves. This is active range of motion. Passive range of motion much less common in our normal daily activities. It requires a person to relax and allow their joint to be moved by an outside force. This force could be gravity, or another person (like a physical therapist), or a machine (like a stretching brace, or pulley). The rotator cuff is a commonly injured tendon. Repairing rotator cuff tears makes up a large part of my practice. I perform this surgery using an arthroscope, and it takes about an hour for me to repair the average rotator cuff tear. Patients usually go home the same day, wearing a special brace to protect the repair. This is where the hard work begins for the patient. Rehabilitating a repaired rotator cuff takes time, involves discomfort, and is not fun. It is also crucial to do it properly. Improperly rehabilitated rotator cuff repairs could result in problems. Inadequate stretching (passive range of motion) could cause stiffness. Too much active range of motion, too soon, could cause the repair to fail. I recommend thinking about rotator cuff rehabilitation as a sequence of 3 main phases:

It is very difficult to completely relax while someone, or something else moves your shoulder. Try to imagine your shoulder is paralyzed. Allow your arm to hang relaxed by your side. Then bend forward at your waist allowing your arm to swing away from your body under the influence of gravity . Keep bending at your waist as far as you can. At this point your arm will be hanging straight down, almost like you are trying to touch your toes or the floor in front of you. Now slowly stand up allowing your arm to gradually return to your side. Try to keep the arm completely relaxed throughout the entire motion. When you are standing upright again and your arm is at your side you are done. Congratulations. You just properly performed a basic passive range of motion exercise. In an upcoming post I will upload a video demonstrating this basic passive range of motion maneuver and a sequence of increasingly complex passive exercises. After this I will demonstrate active range of motion exercises. I never really enjoyed writing. Problem solving was always my thing. Especially if it involved tools/scientific reasoning, and especially physical exertion. My friends and family will surely be puzzled to hear I decided to write a blog.

Throughout my life, I have found myself in a variety of leadership positions. The challenge of solving problems is what drew me to these positions. The ability of a leader to communicate is crucial. It is all too easy to offend or confuse if communication isn't clear. In medical school I realized that some physicians communicate better than others, and that an optimal doctor/patient relationship is driven by good communication. We deal with complex issues, and medical terminology is essentially a foreign language to most laypeople. I observed when speaking with an attending physician, that patients often voiced understanding but gave non-verbal clues that they were confused. Many times the physician was oblivious to this. I made it my goal not to fall into this trap in my practice. I feel my role as a physician is to educate my patients and help them to make the proper decision for them. The paternalistic physician role no longer applies. I believe a collaborative relationship, although sometimes more challenging is ultimately more rewarding for both physicians and patients. As an orthopedic surgeon, my time is divided between my office and the operating room. I perform surgery twice weekly and see patients in my office 3 days per week. Management of orthopedic conditions involves as much art as it does science. Additionally, each patient has a unique set of medical and personal issues that will guide their personal risk/benefit analysis. Communication is the key to a satisfying doctor-patient interaction. A typical day in the office for me involves about 40 patient visits. There is rarely enough time to fully develop these conversations issues to my liking. I do my very best to allow time for questions, to make sure patients understand all pertinent information, and provide additional reading material. I never pressure patients to make a decision "on the spot", but rather recommend contemplating our conversation at home. I feel this leads to a more satisfying experience for my patients. There are a variety of issues that come up frequently. This blog is intended to record my thoughts on these topics. I hope orthopedic patients around the world find this information interesting and helpful. Please recognize that this blog consists of general education only and is not intended to diagnose or treat any specific condition you might be dealing with. Please discuss all medical issues with your personal physician. If you would like a consultation with me either by phone, video call, or in person, please contact me at: [email protected]. |

Dr. GorczynskiOrthopedic Surgeon focused on the entire patient, not just a single joint. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed